Main Paper

Barrington Hall was more than a physical structure. After living in the largest student cooperative in the United States for three years, I imagined it as possibly the largest family home in the country, possibly the world. Cooperative condominiums and their ilk share the financial burdens and the common areas of larger structures among their residents, but within Barrington every social and cultural activity of its 182 residents became a community effort. We ate together, we cooked together, we cleaned together, we sunbathed together, we lived in constant contact with one another, our pets, and vermin we’d only imagined in the suburban homes we grew up in; and we were frequently reminded of our togetherness by stereos roaring through walls and loud parties in hallways late at night. It may be difficult to avoid speaking through youthful idealism or naïveté, but the building known then as Barrington Hall returned more to its occupants than any other structure I have seen, then or since. To many it was an ugly building, painted battleship gray and decorated with by naked pipes, window bars, graffiti and garbage, but its pragmatic ugliness brought it to the level where it could be loved as our simple home, rather than admired for its style and appearance.

I will strive to bring that spirit of Barrington into this paper. The history of the structure is amazingly colorful, and by close analysis we can come to an understanding not only of the workings of the largest group of students then living cooperatively, but perhaps even the changes in American culture itself since the first timbers were raised in 1906.

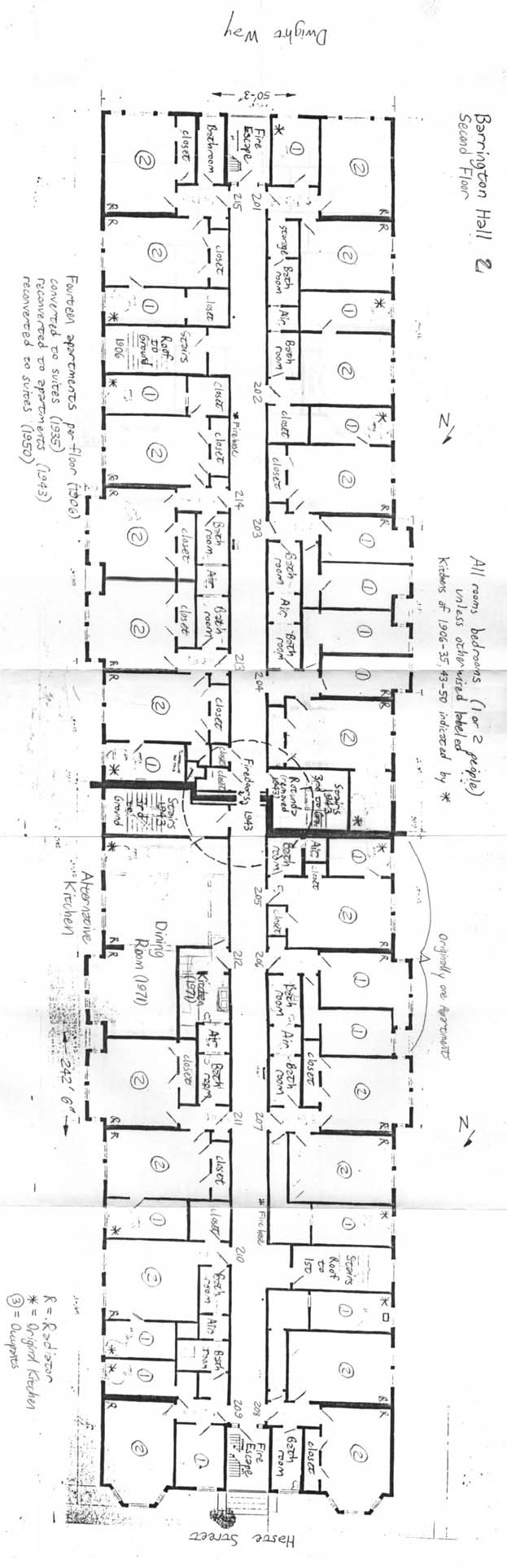

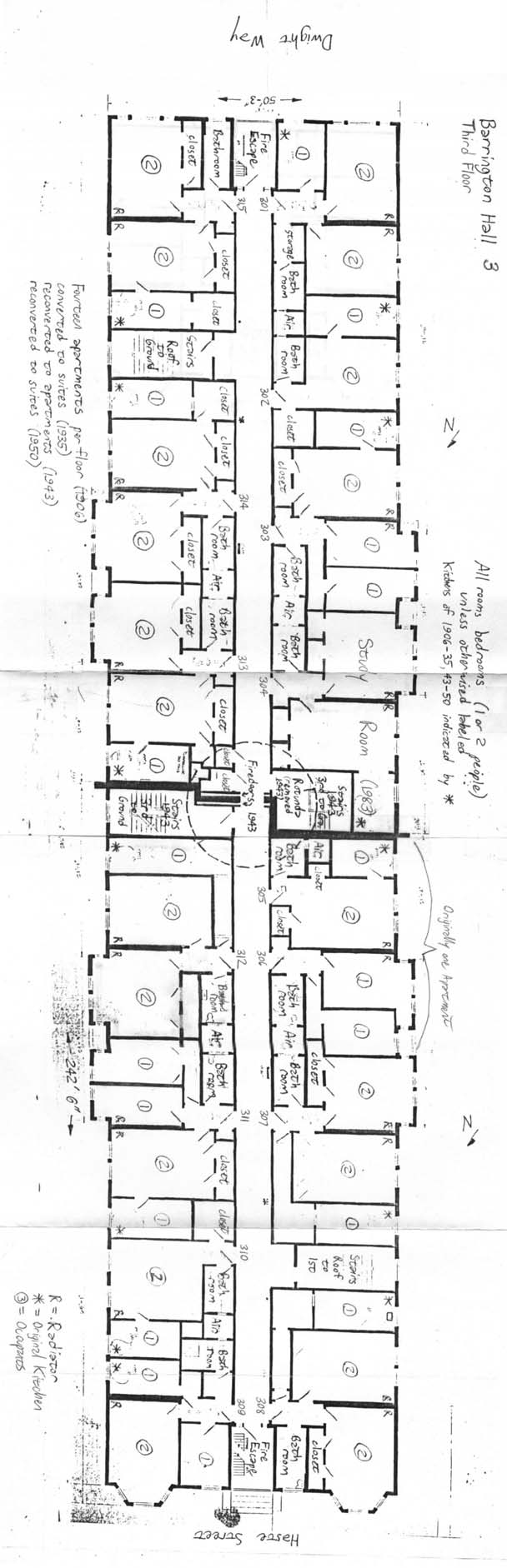

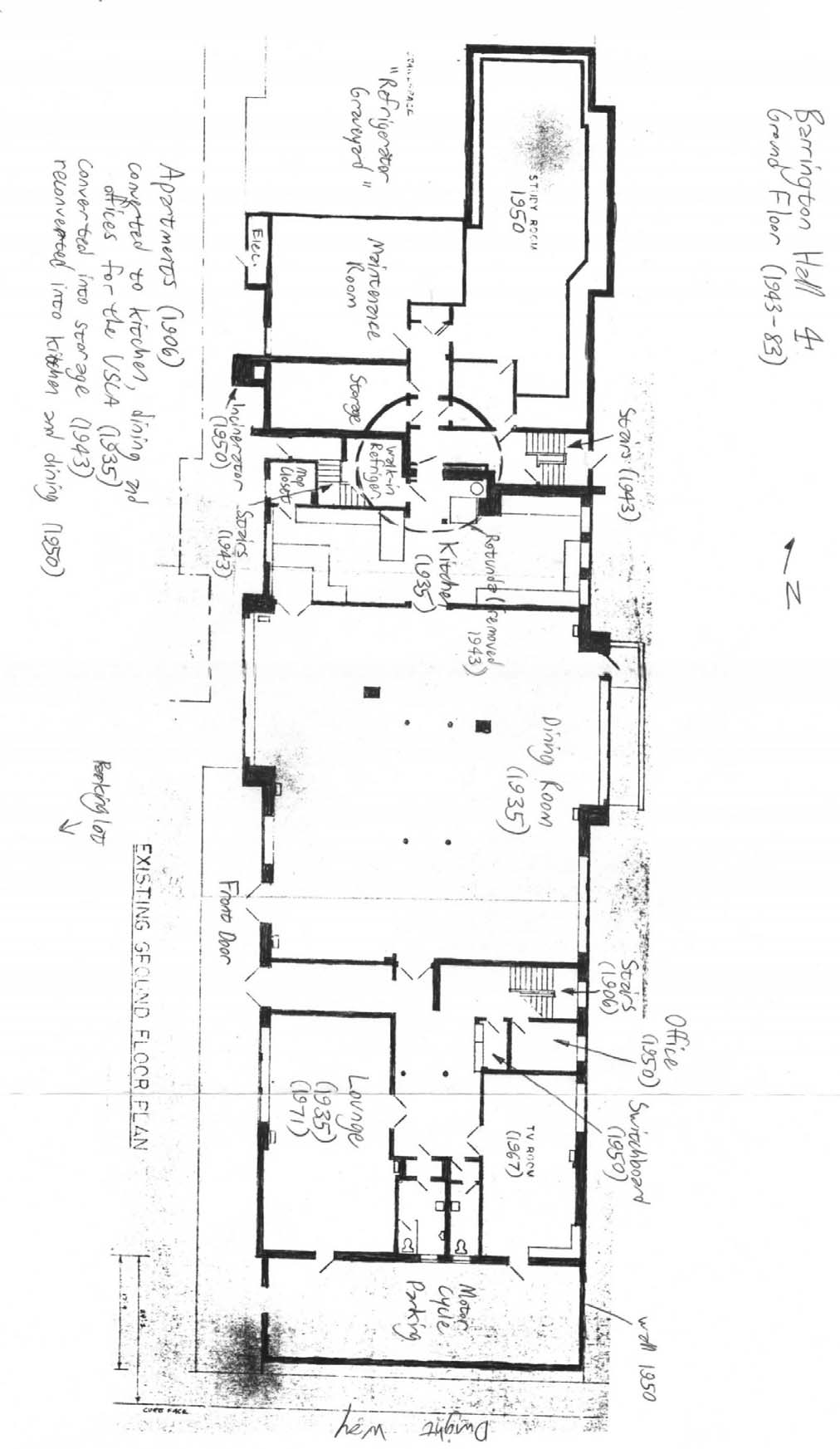

Barrington Hall literally rose from ashes. After the great San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906, a torrent of refugees poured across the Bay to Oakland and the surrounding communities seeking shelter. Under pressure from the city of Berkeley, the University of California allowed construction of an emergency shelter on the College Homestead, property previously reserved for future University housing between the Sather Gate and Dwight Way.1 The shelter was built between Dwight Way and Haste Street just east of Ellsworth Avenue. The property is on a north to south descending grade, so the south end of the building is four stories high, with the north half of three stories resting on a crawlspace about two feet high. The frame is a basic balloon frame on a concrete foundation, many of the principal beams being debris from the San Francisco earthquake. Some of the largest joists, particularly the floor joists above the ground story, have almost an inch of charred wood as a skin, which may seem dangerous but actually makes the beams more difficult to burn. Fourteen apartments were constructed on each of the top three floors, and on the shortened ground floor were possibly seven more. At the very center of the building was an open rotunda with a spiral staircase, about half as wide as the building. Two other staircases are located near the center of the north and south halves of the building, rising to the roof. At each end of Barrington two fire escapes stand at the ends of the corridors that run lengthwise through the structure, so it has an abundance of easy access to all points on every floor. (See Floor Plans 1-5)

The shelter was pragmatic, possibly even temporary structure, at the time of construction the largest residential building in Berkeley.2 Rather than proving a white elephant, however, it became the harbinger of great changes for the city. A massive shift of population to the cities of America was taking place from every part of the world, as well as the general trend of people moving west to California.3 Even though San Francisco was quickly rebuilt across the Bay, the tide of people and the growth of the University continued rapidly to increase the population of Berkeley, which had doubled in just a few years. The Cerone Family, a wealthy sugar family from Oakland, recognized this trend and bought several apartment houses in the East Bay as investments. One was the shelter for earthquake refugees on Dwight Way, which they named the Lafayette Apartments.4 The building was quickly remodeled to accommodate a new breed of Berkeleyites.

The dominant force in architecture just before World War I was the City Beautiful, the philosophy of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, an influential architecture school of the time. Since the end of the Civil War the United States had sought to become a world power; the nation was an industrial giant, a military might, and an imperialist force to rival the old empires of Europe. During the same era, the frontier was beginning to close, railroads and telegraph lines bound cities together, and mechanization permitted thousands to move from the country to the city in search of new work in manufacturing. With such a massive shift from rural domesticity to urban grandeur, a new style of architecture dominated, especially after the introduction of the skyscraper, thanks to the elevator and reinforced steel construction. At the same time, government and non-profit institutions were becoming larger and more stable in the United States, as Reconstruction ended. It was known, even then, as a “gilded age”.

This new style of architecture was a national one that unified the far-flung regionalism of the United States into a single edifice of Technology and Power: the Beaux-Arts. The Parisian Beaux-Arts migrated across the Atlantic Ocean with architects like H.H. Richardson and Richard Hunt, who brought the rational neo-classicism of Viollet-le-Duc to America.5 The Beaux-Arts became an ideal symbol of ancient prestige, power and integrity to the Rockefellers and Vanderbilts who desired it; its intelligent mixture of Grecian, Roman, Renaissance and other Classical forms were meant to represent Beauty itself in a pure form.6

America, however, altered the central ideas of Beaux-Arts to fit an age of rapid construction and expensive labor.7 Capitalism demanded prestige, but at a price affordable to the masses. Instead of marble and stone, brick and wood were made to appear like stone, a violation of the Parisian school’s intention to create a City Beautiful, but also a city that would endure.8 The Cerones followed the local trends in design and in engineering, understandable considering the lack of building resources following the San Francisco earthquake and then the onset of World War I. Their apartment building already had the distinction of being the largest in Berkeley, and with an inexpensive Beaux-Arts façade it would radiate the concept of beauty in American architecture initiated by A. T. Downing in the 1840s,9 thrown into public prominence by the grand Chicago Columbian Exhibition of 1893.10 After all, only a few blocks away the great Beaux-Arts buildings of John Galen Howard were changing the face of the University of California campus. Howard had been a student of Richardson; with this heart of the Beaux-Arts beating so close to the Cerones’ Lafayette Apartments, how could it become anything else but a Beaux-Arts structure itself? Such a design would make apartment living on such a large scale palatable to both students and professors at the nearby Berkeley campus; many other examples from this period abound in Berkeley and across the Bay Area. The exterior of the Lafayette was clothed in redwood, cut and painted to resemble the stone masonry of the University. (See Photos 7, 8, 9, 15)

I must note though, that the ornamentation on the building was not as extensive as on Wheeler Hall, Howard’s masterpiece (Photo 9). In this case frugality saved the Lafayette from being overdone. It was late enough in the Beaux-Arts period for architects to feel the pressures of Modernism, just as the Art Nouveau had devastated the Beaux-Arts influence in Paris,11 and the simplicity of the Bay Area School also had an impact. Craftsman architects like Maybeck and the Greene brothers preached the beauty of naked wood, and they too became major stylistic leaders in California, while Howard decorated the University.12 The resulting amalgam just before World War I was Beaux-Arts with a Mediterranean influence, the first of many stylistic concessions the building then called the Lafayette was to see.13 The interior boasted redwood paneling and hand-turned banisters, and like many Berkeley apartment houses tried to capture the open-air feeling of a Greene and Greene sleeping terrace with an open central rotunda and exterior roll-beds. The roll-beds in particular were a short-lived but interesting addition to many California apartments; built half-in and half-out on an outer wall, by getting in and rolling the cover over, you could sleep outside, if a bit precariously. (Photos 7, 8, 10, 11) The exterior of the building may have appeared vaguely regal, but on the inside it was still firmly rooted in Bay Area tradition. A building meant to house almost fifty families could hardly ignore the feeling of community and environmentalism that even then had begun to seize the Bay Area. Decades before Barrington Hall or the USCA, the Lafayette had started to reflect the group needs of residents over the prevailing architectural trends of the day.

By 1935 the Lafayette Apartments was in a state of disrepair. The disastrous North Berkeley fire of 1923 forced even more refugees into South Berkeley, and the popularity of the automobile and the Key System streetcars (which went down Dwight Way in front of the Lafayette) turned the city into a direct suburb of San Francisco. Telegraph Avenue was rapidly being redeveloped into the urban area it is today. For unknown reasons the Cerones could no longer afford to maintain the apartment house; it had become a gigantic firetrap, with the aged redwood facade ready to go up like a match and the central rotunda a veritable chimney. World sugar production expanded rapidly in the early 20th century, capped by Cuban independence, driving down prices, and with the beginning of the Great Depression, the Cerones were undoubtedly in serious economic straits. With no one else willing to save it, the Lafayette was leased to the young University Students Cooperative Association, which had opened the original Barrington Hall at 2714 Ridge Road in 1933. Armed with their own tools and the new idea of student cooperativism, the USCA made the Lafayette Apartments their new Central Office (CO) and renamed it Barrington Hall, the name of their first cooperative house.14 That Barrington had probably been named for the Barrington Apartment Association in New York City, one of the earliest cooperative “home clubs” in the United States, organized in 1882.15 Where that name originates is even more uncertain, although it may relate to an older co-op in England or in the mill-town of Great Barrington, Massachusetts.

Student cooperativism was not the most radical movement in Berkeley during the time. The city had already been governed by a Socialist mayor, and in the heart of the Great Depression radicalism festered everywhere. The students of the USCA did come together for activist reasons, however; not only for financial benefits, but for what founder Harry Kingman called “a new way of living together”.16 The USCA wanted camaraderie different from the fraternities, one with self-government and diversity. There was no pledge week, no hazing; anyone willing to live and work with 182 fellow students was welcome. Over 1935 the members of the new Barrington demolished the ground floor apartments to build a communal kitchen and dining room, even though they could have afforded to keep the existing apartment kitchens, needing only a communal storage space for food. The space they gained by turning the upstairs kitchens into extra bedrooms was lost by demolishing the downstairs apartments. But the residents wanted to eat together, as an expression of the cooperative ethos.

The house remained a firetrap, without the money to renovate. Nevertheless, the Barringtonians seemed a satisfied, rowdy bunch. They disrupted the annual Big C Parade with a float entitled “Hoover’s Last Erection”17 and caused the city of Berkeley to criminalize water- ballooning when their constant indulgence in that sport demolished the windshield of a police car on Dwight Way.18

Other than continued success as a large cooperative house, not remarkable considering the explosion is college attendance during the period, there were no significant changes at Barrington until 1967. This may seem an odd statement, but I am speaking in terms of the social community relating to the changing building and its architecture. In 1941 World War II came and Barrington Hall fell empty as the male students went off to fight. The building was leased at a minimal rate in 1943 to the Federal Public Housing Authority (FPHA) for seven years, in exchange for badly needed renovations of the entire structure. The FPHA removed the redwood paneling inside and out, covering the outer walls with fireproof stucco and the inside with commercial gypsum boards. The joists were reinforced with steel I-beams. The rotunda and spiral staircase were removed, replaced with two new stairwells and a brick firewall across the center of the building. Finally the suites were turned back into single family apartments and given to Navy workers at the Liberty Shipyard in Richmond, a few miles away by streetcar.19

The USCA returned in 1950 after seven years to a completely remodeled Barrington, much sturdier and unintentionally modern in appearance, through virtue of the façade being removed. Again lack of money strangely kept Barrington in fashion—first economy had tempered the ornamentation of the Beaux-Arts facade, and now economy prevented anything from marring the blankest façade but white stucco. In a way the cooperative had no need for a facade, and decorating the outside was never discussed in council meetings; in fact, the original street entrance was sealed and a six-foot wall erected along Dwight Way, so Barrington was obviously not interested in opening to the outside world, but rather turned in upon itself. The kitchens were once again removed from the individual suites for additional bedrooms, and common areas developed on the ground floor, including the communal kitchen. And in 1967, that common interior finally began to show some signs of social adjustment.

The decision was made in 1966 to convert Barrington to a co-ed house. The progression of events seen in the minutes of the Barrington Hall Council meetings from 1964 to 1967 show increasing disenchantment with the government of the house and the USCA in general. The USCA had moved its main office from the ground floor of Barrington to the new Ridge Project across campus on the Northside. Isolated in the continual uproar of the Southside Sixties along Telegraph Avenue, Barrington started to rebel against centralized control. The system of electing representatives to Council was abolished, with any member choosing to attend having the right to vote. The Judiciary Committee or J-Comm, the internal court system of Barrington Hall, was dissolved.20 With the changeover to co-ed, many rules governing “proper” student behavior were abolished, leaving minor details such as how many pieces of cake to eat and where to eat them to the discretion of the members.

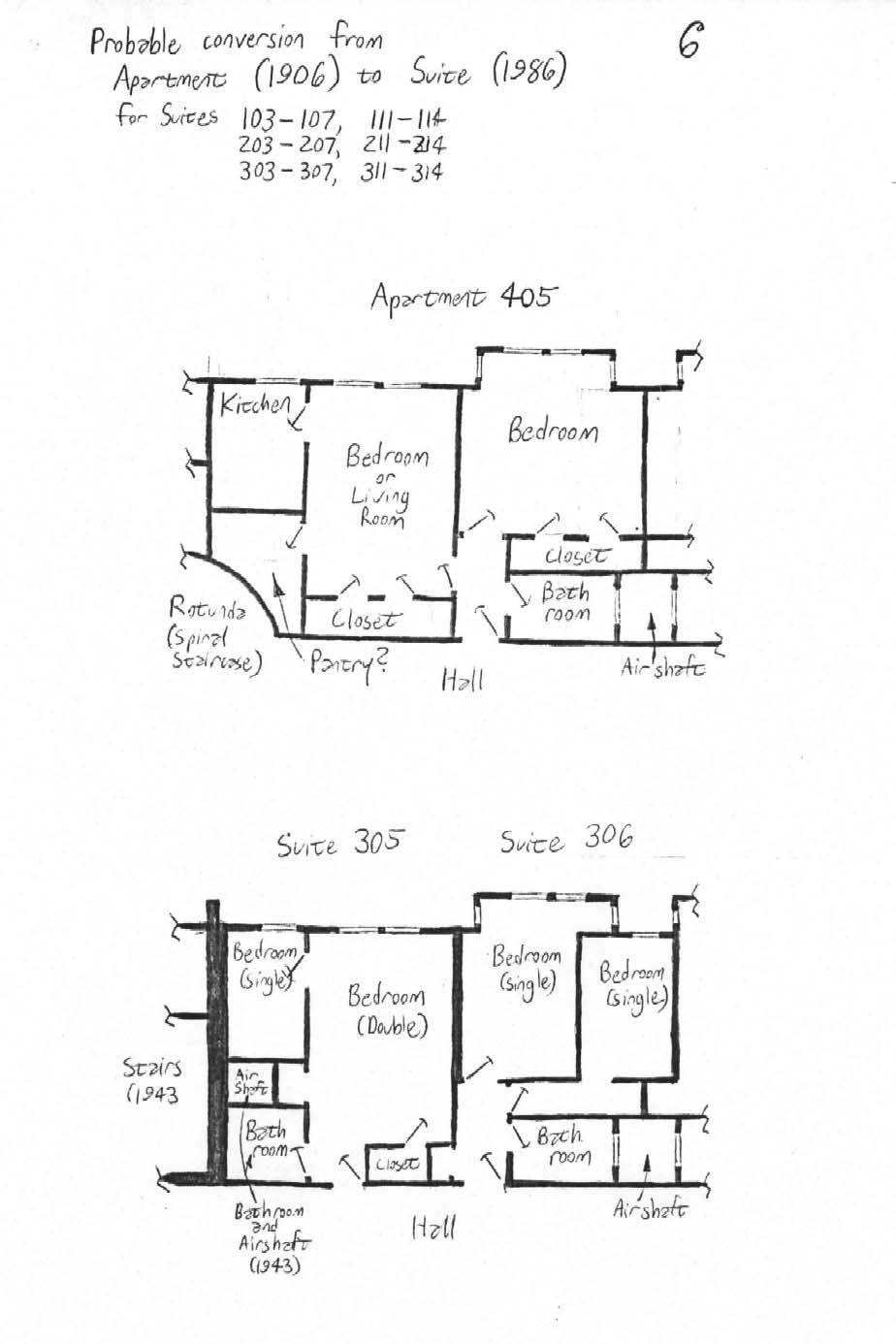

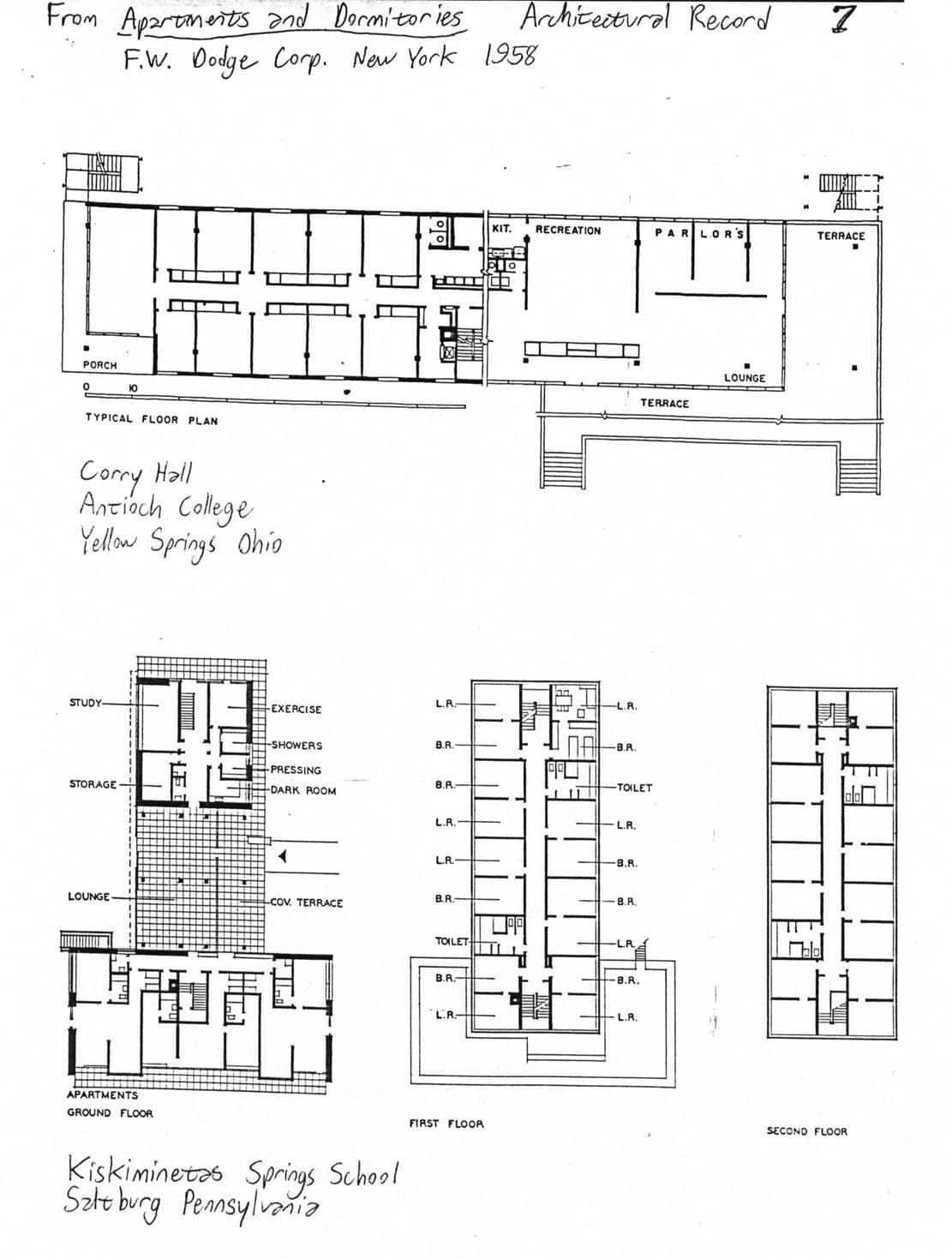

The coming of women to the house immediately caused everyone to “loosen up”. Unlike a co-ed dormitory, where men and women share a common and are paired into rooms, students in Barrington were grouped into suites of two to five people, as well as working together at cleaning or cooking. The house could not be divided by sex easily, even if there had been a desire to, as people who had lived in the cooperative longest had the most “points” and therefore could have the pick of any room in the house, regardless of who their suitemates were. New high-fidelity stereos began to blast through the thin walls that had once separated quietly studying men, but by the late 1960s students found more to do than study anyway. Notice the difference in room access between Barrington and the plans of typical dormitories. (Plans 1-8) Everyone in a suite was channeled through a single foyer into several bedrooms and came into frequent contact—if this had not been the intention, the house would probably have been redesigned after women were allowed in. Typically men and women were paired in the doubles, with a member of the same sex in the walk-through singles (which can be accessed only through a double.) But as noted, regular singles were up for grabs to the person with the most points, and by the 1980s some couples did arrange to occupy doubles, so the mix of singles and couples, men and women in most suites was unusually diverse even for Berkeley student life.

Possibly the most significant cultural alteration in the house began with the painting of the Yellow Submarine mural on the wall across from the second floor landing of the south stairwell. Inspired by the Beatles and the psychedelic drugs coming over the Bay Bridge from the Summer of Love in Haight-Ashbury, murals were gradually painted in the halls after 1968, until by the early 1980s there was not a single white wall in any of Barrington’s commons areas, the halls, dining rooms, council rooms, the study rooms, the roof, etc. The appearance of community art marked Barrington as culturally curious, even rebellious. The building, with help from the residents, manifested a peculiar environment, in effect welcoming drug experimenters, political radicals, musicians and artists into a contained space. The blank exterior façade and wall across what had been the entrance enforced a sense of separation or cliquishness, while the unusual co- ed layout of the suites and the painted hallways advertised a safe haven for the counterculture.

By the time of the People’s Park Riots in May of 1969, Barrington Hall was an infamous place in Berkeley. The devotion to cooperation in a nation committed to competition bore radical fruit after thirty-five years. Barrington became a “safe house” for deviance, good or ill. It was safe for unmarried men and women to live together, safe to paint and draw on the walls, safe to do or sell any drug, safe to crash in if you had no other place to stay. Of course, not everyone living in the house agreed with this lifestyle, in 1970 or in 1990. But Barrington Hall is a large building, with almost 130 bedrooms, multiple stairwells, a large accessible roof, and until 1983 a closed-in backwater on the ground floor where anyone could do anything unobserved. The main entrance was located off the dining room, meaning that most the traffic south of the dining room was simply crossing the five feet to the south stairs. (Plan 4) The rest of this common area was essentially a hotel for street people, and the anarchic government of the house was unconcerned. After all, thousands of hippies poured into the Bay Area for the Summer of Love and remained throughout the campus rioting at Berkeley and San Francisco State University. Barrington caught the eye of radicals by banning police from the house after they ran through the halls in 1968, and the local chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) was formed in the building. Barrington became the capital of Berkeley’s counterculture, and even as recently as the 1980s was the home of the SAFE organization against fee increases and the Biko Plaza News, the underground press of the anti-apartheid movement during the occupation of Sproul Plaza on campus.

The exterior facade was still ignored by those living inside throughout the 1970s. It was a blank face to the outside world, cutting the structure off from the street, the neighbors and the auto traffic up Dwight; the streetcar was long gone. The building was unsecured and open, if not inviting, to pedestrian traffic, but wild murals and garbage on the interior were as effective as an electrified fence in keeping out the “uncool”. The residents apparently had the situation where they wanted it, and by simply maintaining the appearance of the building as the status quo, the new members were confined within certain limits of personality, a new radical “norm” which made the residents highly compatible. Ritual and romance rose up over the dying 1960s, and this new Barrington spirit carried through the culturally vacant 1970s into the changes of 1980s. The building, in essence, had created its own perpetual legacy.

In passing I should note the one physical change made in this period, the conversion of Suite 212 into the Alternative Kitchen. This room, quietly tucked away on the second floor, is the abode of the house’s vegetarians, and the “AK” was the only construction meant to accommodate a new type of resident.

In 1970 the USCA decided to decentralize its budget, which permitted the houses to spend as they pleased against a budget, rather than being allotted money from the Central Office (CO). With aggressive fundraising and growth, the co-op was over a thousand members and unwieldy for such centralized control; there was also much suspicion of authority in the USCA and Berkeley in general with the violent end of the 1960s. In retrospect the complete decentralization was a major error on the part of the CO. No one at any of the houses was properly trained to handle their own budgets, and the more anarchic houses went thousands of dollars over budget. Through seniority, the most skilled managers had left the large houses for smaller co-ops like Davis House or Rochdale Village, the apartment complex completed by the USCA in 1971. Barrington Hall kept afloat financially in the late 1970s by becoming an unlicensed nightclub on Saturday nights. Fatefully coinciding with the rise of punk rock, Barrington provided one of the only venues for early punk bands in the Bay Area. Influential groups such as X, Black Flag and the Dead Kennedys played their first Berkeley shows at Barrington, and the money charged at the door kept the house in the financial black. In addition a new type of student, confrontational young punks, were thus attracted to the house. Times were changing. Like hippies in the 1960s, punk was a reaction to growing conservatism in the United States, and this conservatism began to pressure Barrington. The blank façade sported such graffiti as “Go Away” and “Fuck You All”, and the house finally suffered a backlash. The neighboring Elsmere Apartments took the house to court over noise complaints in 1982, and the nightclub was closed. To make matters worse, the drugs of choice in the United States, Berkeley and Barrington changed from the more artistic and benign marijuana and LSD to the destructive cocaine and heroin. Without revenue from the shows and increasing embezzlement by drug addicts in management, Barrington’s finances fell rapidly into the red.

In 1983 the first “rehabilitation” of the house took place under the guidance of the CO, who realized sixteen years too late that they had lost control of the larger co-ops. Beyond some minor cosmetic changes, a major effort was made to change the building culturally. Compare Plans 4 and 5 as we see what the Central Office tried to accomplish.

The Study Room was moved from the ground floor to Suite 304 to make it slightly more comfortable, but primarily to eliminate the former Study Room as a hiding place for street people, as it had been the most isolated room in the house. The TV Room, another “den of iniquity”, was removed from the building altogether and turned into a Bicycle Room. The office was enlarged to establish a stronger administrative presence in the anarchic house, although there was still no guidance on management from the CO. The Switchboard was moved to the new entryway onto Dwight Way. The old Switch, next to the south stairwell, was a popular hang-out, with much of the building’s evening traffic passing by. After the 1983 rehab it could only be accessed through the Bike Room and stood guard over the entry, one of the new responsibilities of the switchboard operator.

Most significantly, the Entryway was moved from the side of the house to the front once again, to end the backwater around the lounge and to improve the façade of the building, which it admittedly did. Barrington Hall now opened onto Dwight Way instead of the parking lot, as it originally had for decades, and resembled a normal apartment building. There was no longer any “hiding” in the Lounge, which in a sense became the foyer of the structure. The result was something of a backlash on the part of the residents. Barrington was our home—we had thought we had made it, and more importantly, it had made many of us; for some people it irrevocably changed their lives, good or bad. The social activities of the building reflected our attachment to the cooperative and its recent history. Studying was usually done in the central dining room, not the isolated Study Room on the third floor. Even three years after the Rehab, when this study was completed, most residents entered the building through the parking lot door (usually propped open) into the dining room, the public space where most people congregated, while the locked entry on Dwight remained quiet. Parties were rarely held in rooms, but in the dining room or often in the hallways, where to get through you might have forded a tangle of thirty or forty legs in the dark. All of the stairwells were coated with graffiti, these common areas being the barometers of house opinion. The Lounge remained dormant except for occasional movies on TV and the Council, the rowdy Sunday night meeting where anyone interested came to make decisions on house policy and catch up on the week’s gossip.

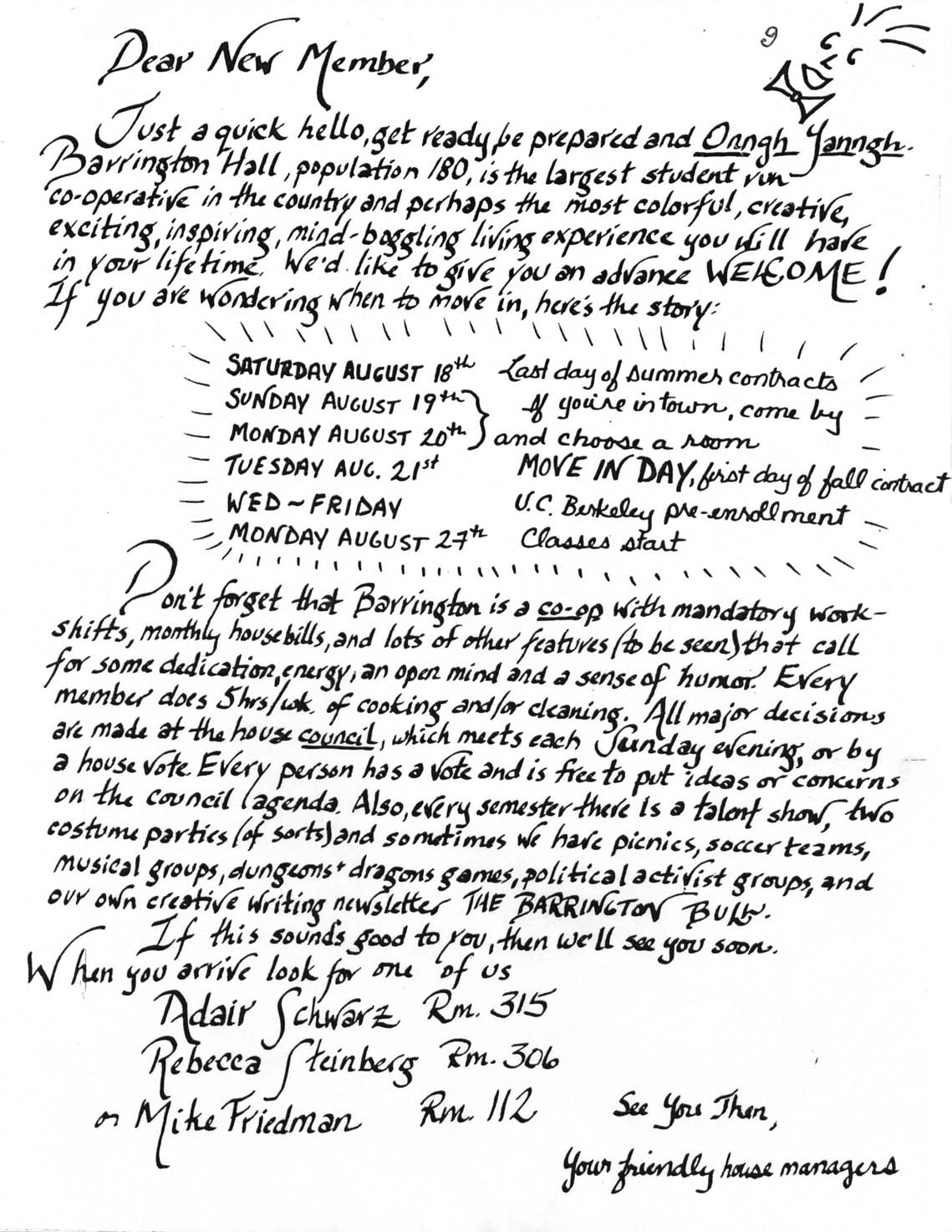

A second rehabilitation occurred in the summer of 1986, when the structure was emptied, cleaned and repainted. Drug abuse and dealing in the house had reached a chronic level, and both two overdoses and many continuing complaints by the neighbors created interest in Barrington from the police and the City Council. At the same time the city of Berkeley was transforming, becoming wealthier and more conservative as San Francisco grew exponentially through the “dot bomb” of 2000. Younger visitors, most of high school age, began to tear up Telegraph Avenue and places like Barrington Hall in the early 1980s; their graffiti spread from the stairwells and began to destroy the historic murals themselves. With the liability insurance of the entire cooperative on the line, it was only a matter of time before Barrington Hall was closed to students, leased and completely painted, inside and out, after a violent confrontation with the police. The only surviving murals are the “Last Supper” in the AK and some minor graffiti in the Maintenance Room. And two other houses, Cloyne Court and the Chateau, have both come under similar scrutiny—evidence that Barrington was not the cause of its own destruction, but simply the first victim of its size and the mismanagement of the USCA.

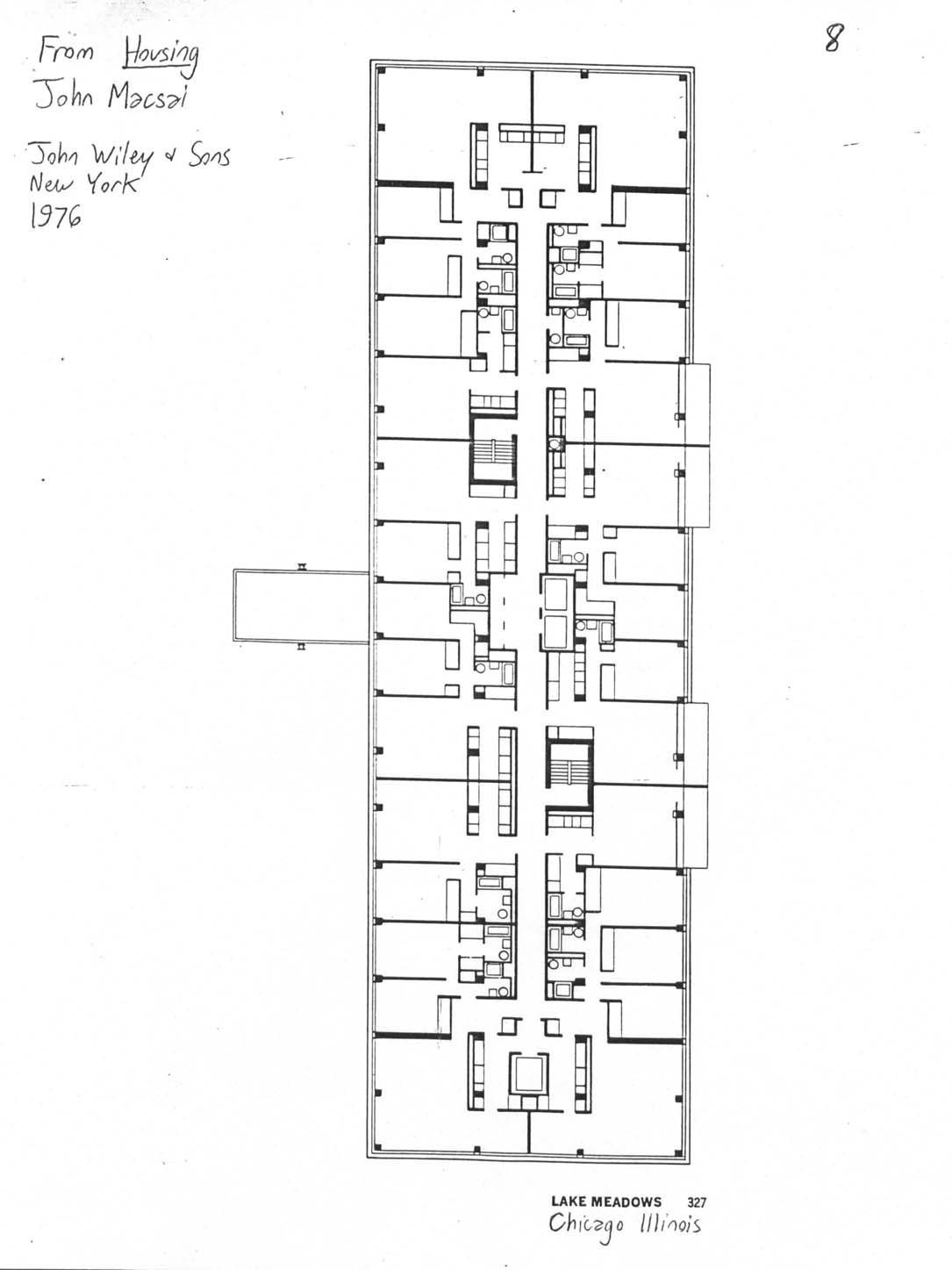

Barrington Hall was not a work of art. Barrington was a building we painted and used as best we could to be a cooperative house. People vented their feelings by kicking holes in the walls, and then showed their devotion to the house by lovingly repairing and decorating the walls. The Central Office tried to reorganize the commons to subdue us, converted doubles and walkthroughs into singles to isolate us, but nothing worked. The architect Robert Venturi described symbolism in architecture as the major visual form of communication. I would extend this statement further and claim architecture itself to be a kind of communication, if it is flexible enough. Why else would we say, “building a wall between us”? We transform space, and architecture organizes that space. Simple ideas, but in writing of Barrington’s “style”, we lose sight of the simple facts. Barrington was just a large apartment building. Instead of broadcasting a single style, it was stripped bare, providing an ideal canvas for individual style; our space flaunting itself, saying THIS IS OUR HOUSE, but in Barrington Hall our energies were not devoted to the style of most significant features of our façade. If you study the house carefully, the most salient original feature is the pattern of the windows, the design of the openings to the interior, but we did not modify the windows, because the message THIS IS OUR HOUSE was directed towards ourselves and our guests. The house was our primary method of communicating our unity as a cooperative, as we were all contained within its filth and its beauty. Throughout the long history of Barrington Hall it has been adapted, not so much to any vague notion of style, but to the defined needs of those who live within. The Beaux-Arts façade of 1906 was simply a concession to a time of patriotic rebuilding and classical rebirth in the Bay Area. When the building was the Lafayette, it was designed to centralize the occupants of each apartment (as in the modern plan 8) through the spiral staircase; later the design was configured to centralize the entire building into the downstairs commons. We took full advantage of what we had been given, because we felt the house was ours. We spoke to each other through the medium of Barrington Hall, and indeed, because of this dialogue the house spoke back. To the discredit of all of us, we made Barrington vulnerable to the changes going on around it, and the house as a community ceased to exist. But the building still exists, a long gray battleship between Dwight Way and Haste Street, and until the last Barringtonian is gone, I hope it will persist in our dreams.

For Peter Spencer and my family at

Barrington Hall 1983-1987

Bibliography

- Architectural Record, Apartments and Dormitories. FW Dodge, New York 1958

- Robert Bernhardi, The Buildings of Berkeley. Lederer, Street & Zeus, Berkeley 1971

- John Burchard, The Architecture of America. Little, Brown & Company, Boston 1961

- Harold Bush-Brown, Beaux-Arts to Bauhaus and Beyond. Watson-Guptill, New York 1976

- Erika Dreisch, “Illusion in Beaux-Arts” Architecture 271 Dr. Kostof 29 August 1969

- Max Ferro, Evolution of Masonry Construction in American Architectural Styles. Sermac, Chicago 1976

- Ira Fink, Apartments in the Berkeley Campus Environs. University of California, Office of the President, Berkeley 1973

- David Handlin, The American Home. Little, Brown & Company, Boston 1979

- Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Architecture Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Penguin, Baltimore 1967

- ILWU Longshoremen Redevelopment Corporation, St. Francis Square. San Francisco 1963

- Institute of Real Estate Management, Cooperative Apartments. Chicago 1961

- Guy Lillian, A Cheap Place to Live. University Students’ Cooperative Association, unpublished 1973

- John Macsai, Housing. John Wiley & Sons, New York 1976

- Marcus Wiffen, American Architecture. MIT Press, Cambridge 1983

Photographs and Drawings

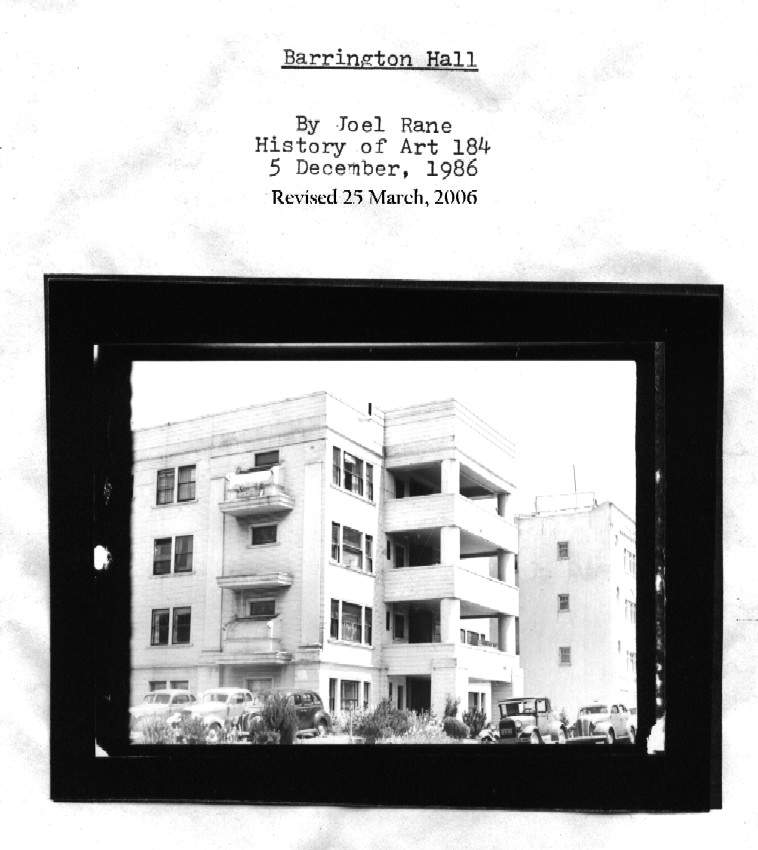

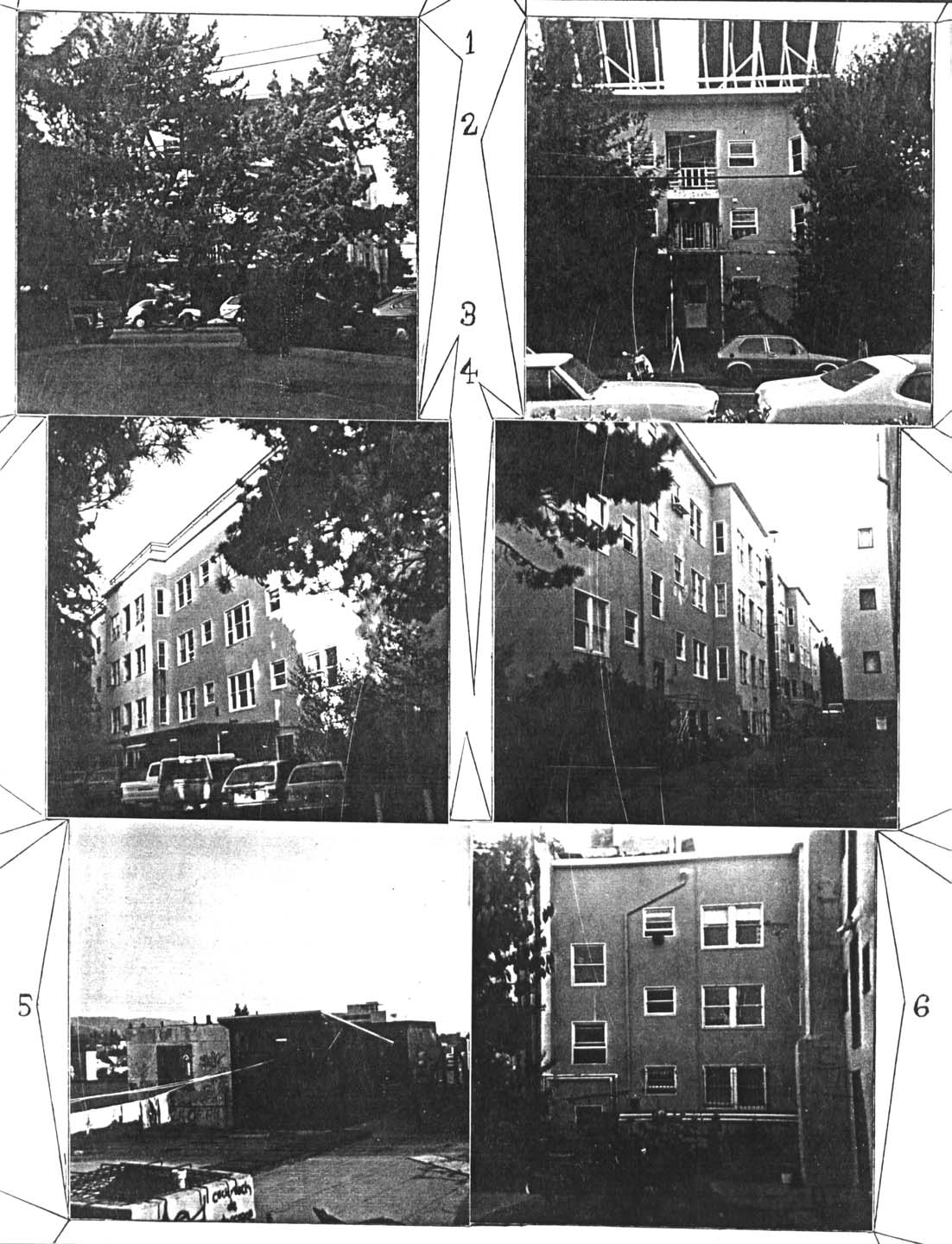

- The south side and main entrance to Barrington Hall, at 2315 Dwight Way. The building was sheltered behind two healthy trees, later removed, and a small garden, as opposed to the six- foot concrete wall that fronted the sidewalk until l983. Notice how the original balconies were removed from the front in 1943, the only balcony now being the metal fire escape of the first floor. The façade of the ground floor—windows, overhang, doorway and mural—were new. This space was sealed between 1943 and 1983.

- The north side of Barrington Hall facing Haste Street. Here you see more clearly details of the fire escape and the bay windows. The door opened into the first floor, as the ground floor only reaches the center of the building due to a north-south grade. On the roof two of the four sets of solar panels added in 1985 are visible.

- The west side of Barrington Hall, and the parking lot. The entrance from 1943 to 1983 was under the overhanging roof; this became a secondary entrance.

- The east side of Barrington Hall, showing clearly the unusual size of the building. Notice the various “additions” to the exterior, such as the new steps on the left, the exhaust tower for the boiler room and the horizontal pipes carrying water from the solar panels to the boiler.

- Part of the roof. This view is towards the southeast. The white shed was the original laundry room (1935), the wooden shed being a 1983 addition. The smaller unpainted wooden box was a sauna. The top of one of the eight airshafts can be seen in the foreground. The firewall installed in 1943 juts up on the right, being crossed by a stile. This stile, built by this author in 1984, remains to this day. The solar panels are directly behind you. There are two access points to the roof, the north and south stairwells.

- Barrington as seen from between two of her neighbors. The amusing collection of pipes, bars and windows made our home look rather like an oil refinery or a pretentious art museum.

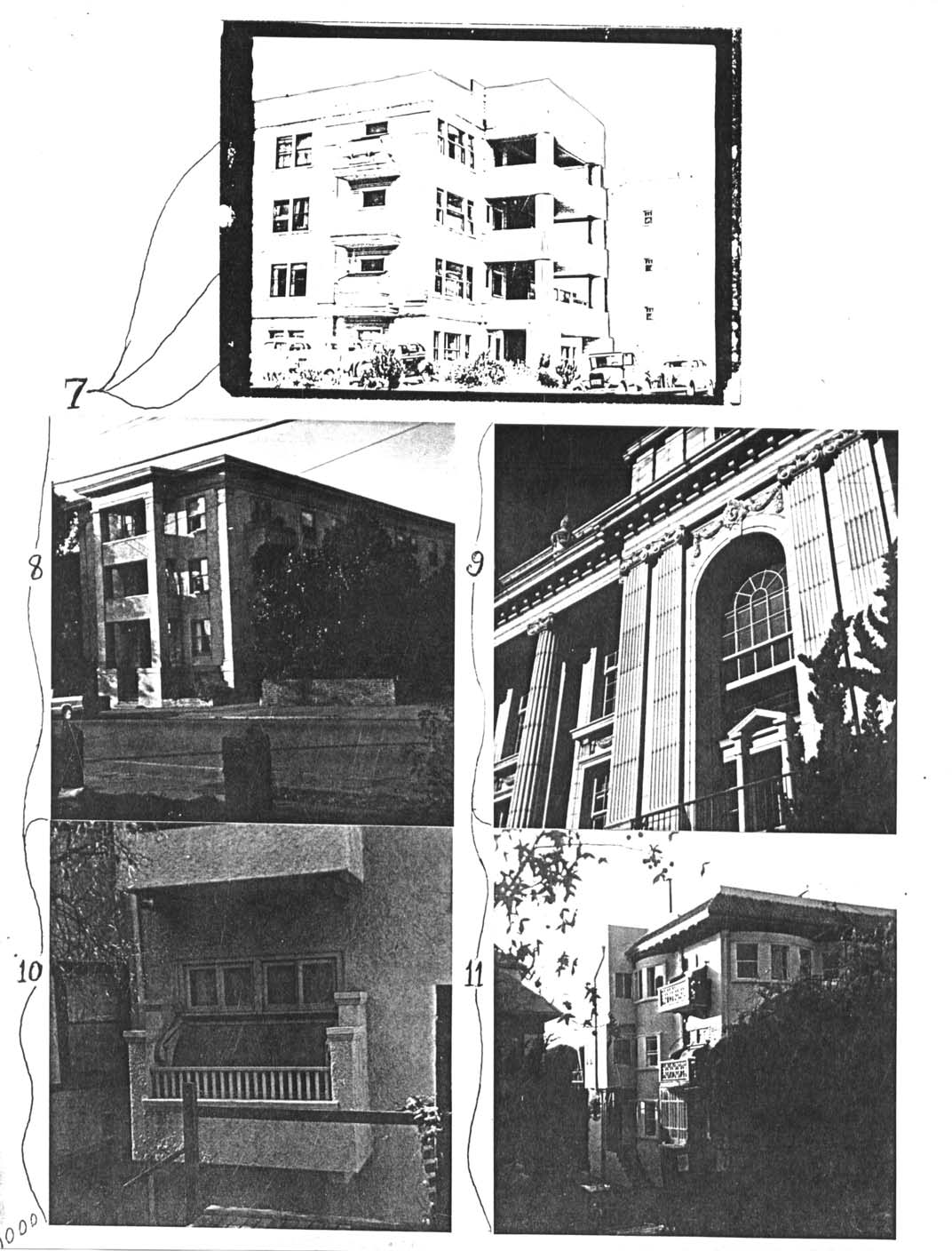

- Barrington Hall, south entrance, in 1935, shortly after it was leased to the USCA. The façade is original from 1906, except for the missing capitals. The façade is redwood painted to imitate the Beaux-Arts style of John Galen Howard.

- A building similar to Barrington Hall, but somewhat smaller, on Channing Way west of Dana Street. The roll-beds have been converted to balconies.

- John Galen Howard’s Wheeler Hall, on the Berkeley Campus. This structure came twelve years after Barrington was finished, but shows fairly well what the Cerones wanted to imitate. The half-pillars flanking the arched window are most typical of Barrington’s Beaux-Arts “gingerbread”.

- A roll-bed, at Treehaven on Ridge Road east of Euclid Avenue.

- More roll-beds on Dana north of Haste Street.

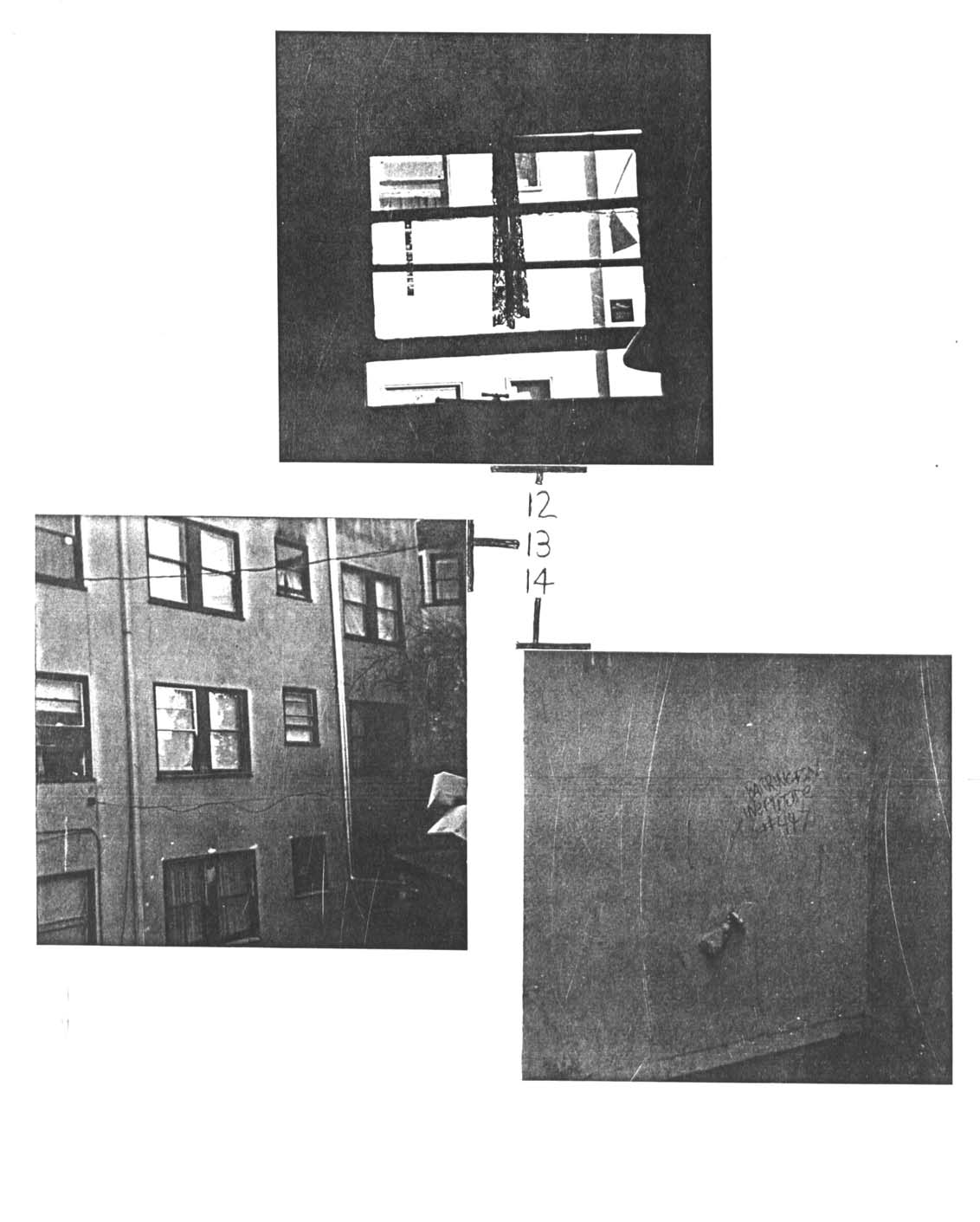

- The lovely view from a standard Barrington window. This was my room; I love the urban life.

- More amusing fenestration patterns in the USCA. This is the back of Stebbins Hall, a contemporary of Barrington on Ridge Road.

- “Barrington Ineptitude #447”. A souvenir of the stuccoing of 1943. Such mistakes, like sealing a faucet, are not uncommon in any stuccoing.

- Another anonymous contemporary of Barrington Hall, in the golden age of the apartment house.

Floor Plans and Miscellany

- Barrington Hall, first floor.

- Barrington Hall, second floor.

- Barrington Hall, third floor.

- Barrington Hall, ground floor, 1983.

- Barrington Hall, ground floor, after the rehabilitation of 1983. Pay particular attention to the changes in traffic patterns.

- A typical room conversion, from apartment to cooperative suite. Notice how space is maximized and personal interaction becomes almost mandatory.

- The floor plans of two college dormitories. The residents are much more effectively isolated in these buildings from one another.

- A modern apartment house very much like Barrington. People living in different bedrooms are directed into the center of the apartment by the design.

- A cheerful welcome note, dated a year after the rehabilitation of 1983. The shadier side of Barrington Hall has been left out.

- The USCA contract from 1984.

Footnotes

- Guy Lillian, A Cheap Place to Live. University Students Cooperative Association, 1973 (unpublished), p. 7.

- Ibid, p. 9.

- John Burchard, The Architecture of America. Little, Brown & Company, Boston, 1961, p. 208.

- Lillian, op cit, p. 12.

- Henry-Russell Hitchcock, Architecture Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Penguin, Baltimore, 1967, p. 170.

- Erika Dreisch, “Illusion in Beaux-Arts”. Architecture 271, 29 August 1969 [Dr. Kostof], p. 1.

- Burchard, op cit, p. 225.

- Burchard, ibid., p. 250.

- David Handlin, The American Home. Little, Brown & Company, Boston, 1979, p. 235.

- Hitchcock, op cit, p. 230.

- Hitchcock, ibid., p. 306.

- Robert Bernhardi, The Buildings of Berkeley. Lederer, Street & Zeus, Berkeley, 1971, p. 47.

- Bernhardi, ibid., p. 41.

- Lillian, op cit., p. 24.

- Richard Siegler and Herbert J. Levy, Brief History of Cooperative Housing. National Association of Housing Cooperatives, p. 2. http://www.coophousing.org/HistoryofCo-ops.pdf

- Lillian, ibid., p. 21.

- Lillian, ibid., p. 40.

- Lillian, ibid., p. 43.

- Lillian, ibid., p. 79.

- Lillian, ibid., p. 102.