Prologue

As a member of the U.S.C.A., I have long heard snippets of stories about the infamous Barrington Hall. As a former member and aficionado of a large U.S.C.A. house, Casa Zimbabwe, which was also at one time considered the scourge of the U.S.C.A., I felt a sympathy for and identified with the stories I heard about Barrington. Learning of some of the exhilarating and often crazy antics of the house, I was struck with the desire to know exactly what happened at Barrington Hall. To me stories of the house seemed a little out of control, but also seemed familiar and close to one part of the college experience that I, myself, enjoyed. Why would the U.S.C.A. go to the extreme measure of shutting Barrington Hall down? The following, with information collected from a variety of sources including old U.S.C.A. newspapers, old Barringtonians, and more, is what I discovered as the story of Barrington Hall.

Krista Gasper

Summer 2002

Thesis guidance was provided by Reginald Zelnik.

Introduction

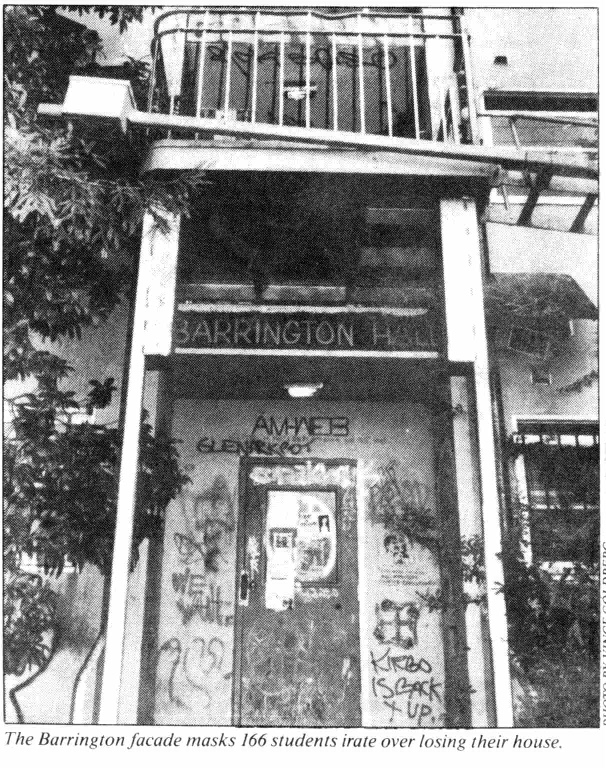

At the location of 2315 Dwight Way sits Evans Manor, a building that stretches the entire block between Dana Street and Dwight Way. It is a quiet, private residence hall where students can be seen walking through pristine hallways where white walls are interrupted only by red doors. It is an average college-town building; behind the doors live students who rent the rooms. If one were to ask the students what they thought of the residence hall, most would say, “It is a nice place to stay while in college.” Few, if any, would know the history of the hall that had previously been the scourge of the neighborhood. Few would know that only a decade earlier, Evans Manor was covered with graffiti on the inside and outside and had the reputation among the community as a den of drug activity. The Evans Manor residents might be shocked to discover that their building was once a hotbed of counter cultural activity, and the people who lived there fought tooth and nail to keep their counterculture alive. Some neighbors most likely remember when the building claimed the name and spirit of Barrington Hall. Few who knew it actually can forget it, especially those who experienced everyday life within its walls. Even coopers now know of the infamous Barrington. When the name is mentioned, a gleam of excitement enters their eyes and the words they so long to say about Barrington Hall bubble to the surface; everyone has heard something about the place.

What Was the U.S.C.A.?

Barrington Hall was a house in the University Students Cooperative Association, the U.S.C.A. The U.S.C.A. traces its beginnings to 1933 when a group of fourteen students at the University of California, Berkeley, collectively rented a house, purchased food and performed house chores. These students hoped to provide themselves with an affordable place to live during the tough era of the Great Depression. They were following the lead of other students, like those in Ann Arbor, Michigan, who were banding together to sustain themselves by creating cooperative housing.7.1 These student groups were part of a worldwide cooperative movement of people who hoped to provide goods and services for themselves more cost effectively by working together.

The U.S.C.A. made it through its first years as an organization through the hard work and sacrificial efforts of its members. They pooled their own money and applied for loans from the outside world to purchase a residence in 1934. They soon purchased other houses and increased the membership of the organization. The houses incorporated as a business providing cooperative housing. Throughout the 40s, 50s, 60s and 70s, the U.S.C.A. continued expanding and, by the 1980s, the population totaled around 1400 members living in 18 houses or apartment complexes.7.2

The organization expanded in ways other than size. Members saw the U.S.C.A. as being on "the leading edge of progressive culture. Most likely because it was run by students who were learning new ideas, the U.S.C.A. served as a catalyst for innovative ideas in Berkeley. It was the first housing organization to allow minorities to fully participate, and the first organization to allow co-ed housing of students.7.3 In both the Free Speech Movement and protests against the war in Vietnam of the 60s, many U.S.C.A. members participated actively. Mario Savio, for example, one of the most well known leaders of the Free Speech Movement, was once a member of the U.S.C.A. house Oxford Hall.7.4 Many U.S.C.A. members prided themselves on involvement with radical movements. In fact, most U.S.C.A. houses had a “Bail Funds” account to bail protestors out of jail. To express its progressive sentiment, the organization adopted the following as its mission statement.

The purpose of the University Students’ Cooperative Association (U.S.C.A.) is to offer low cost, cooperative housing to university students, thereby promoting the general welfare of the community and providing an educational opportunity for students who might not otherwise be able to afford a university education. The organization is committed to educating and influencing the community in order to eliminate prejudice and discrimination in housings.7.5

This statement verbalized the philosophy that underlay many U.S.C.A. traditions, that is, the organization was actively open to all breeds of people and their ideas.

In addition to adopting its own mission statement, the U.S.C.A. was shaped by the mission statement of the cooperative movement, as a whole. The cooperative movement originated in Rochdale, England in 1844, where a group of men and women pooled their resources to open a dry goods store at which members could buy needed supplies at or slightly above cost. The Rochdale Pioneers, as they were called, many inspired by the social utopian visions of Robert Owen, hoped to create a means for democratically controlling their own resources and the prices and quality of the goods they purchased. Out of their original idea of democratically working together to maximize benefits, a whole movement was spawned. Today millions of cooperatives exist, providing services and goods to those who need them. Housing, purchasing, marketing, worker, daycare and many other types of cooperatives in hundreds of countries across the world make up the international cooperative movement.7.6

Members of the co-op (short for cooperative) movement were in the past, as they still are today, linked by their adherence to several principles which were valued by the original Rochdale Pioneers. Drafted in 1966 by the International Cooperative Alliance, these principles were known as the Rochdale Principles. The first of these principles was open and voluntary membership. For the U.S.C.A., this principle translated to mean membership open to all people regardless of race, religion, ethnicity or political affiliation. The second principle, member economic participation indicated that each member shared in the ownership of the organization by making monetary and labor contributions. Democratic member control was the next principle of cooperatives. Each member of a cooperative had an equal vote, which gave him/her an equal say in running the organization. Under the fourth principle of autonomy and independence, cooperatives strived to be as independently controlled as possible. For the U.S.C.A., this meant members were allowed to make decisions without any other organization directing their actions. A fifth important cooperative value was education, training and information. Under this principle, the U.S.C.A. tried to provide its members with as much information as possible including how the organization works, decisions made by the organization, how the U.S.C.A. fits into the student and world cooperative movements, and how members can participate in their micro and macro communities. The sixth Rochdale principle was cooperation among cooperatives. Just as co-op members joined together to mutually aid each other, cooperative organizations were encouraged to support one another, financially, politically, and otherwise. The final Rochdale principle, concern for community, delineated the common goal of community building. Like all cooperatives, the houses of the U.S.C.A. concerned themselves with building a supportive, functional community within the co-op as well as a respectful relationship with other community members and organizations.7.7

The seven Rochdale principles influenced the culture of all U.S.C.A. houses to varying degrees. U.S.C.A. members were at least aware of these principles, even if they were not always directly quoted as a reason for making decisions. They were often transmitted via co-op practices like voting in elections or voting at house council, rather than directly spread as a formal philosophy; though many houses did display a poster of the principles, and they were included in the U.S.C.A.’s Owner’s Manual.7.8 Barrington Hall’s constitution and bylaws, which were distributed to but not necessarily read by every member, included a list and explanation of these principles.7.9 Barrington, like other U.S.C.A. houses, shared in the spirit of the Rochdale principles.

The philosophy of the U.S.C.A. was expressed in the way it was run. A Board of Directors who supervised a staff of several employees, the Central Level staff, ran the U.S.C.A., as a whole entity. The Board of Directors (Board for short) made decisions that affected the entire U.S.C.A. membership. Board dealt with rent increases, U.S.C.A. policy changes, and problems that affected the entire organization. The Board, itself as controlled by all U.S.C.A. members through elected Board Representatives. Each house sent one Board Rep (short for Board Representative) per fifty house members to represent the house in the U.S.C.A. decision-making process. The Board Reps had the responsibility of ensuring the continuity and viability of the U.S.C.A. as a whole. Also sitting on the Board of Directors were a president, several vice-presidents and a few Central Level staff members. These non-Board Reps provided needed information to the Board Reps, helped direct the organization, and made sure that the decisions made by the Board were implemented. They did not vote on proposed items; only the Board Reps had a vote.7.10Under this system, the power to make decisions rested in the hands of the Board Reps, who were accountable to the members of their respective houses.

Individual houses were governed by a house council made up of the house members in attendance. A certain number of house members, called quorum, must have attended for the house council to make decisions. Quorum for Barrington was the House President, Vice President and eight house members. The house council made decisions affecting the house’s financial affairs, such as how much money was allotted for a party, house policy such as the creation of new bylaws, and other aspects of the house. The house council designated what constituted a finable offense for the house. It also decided who was considered a threat and not welcome to the house. The house council provided input to the Board Rep on U.S.C.A.-wide decisions. Minutes for all house council meetings were taken and posted so all house members could see the decisions made.7.11 House council represented the voice of the house.

House responsibilities and duties were administered and implemented by house level managers. A House Manager oversaw the operations of the house, helped resolve conflicts within the house, and made sure house members had rooms, keys, furniture and other necessities. A Workshift Manager delegated and oversaw member workshifts. Workshifts were the five hours of chores, which every member was contractually obligated to do. They included cooking dinners, cleaning the house and doing maintenance at the house. A Maintenance Manager supervised a maintenance crew, which maintained the structural integrity of the house. The maintenance crew fixed windows, doors, lights and other broken items. A Kitchen Manager made sure the kitchen facilities at the house stayed clean and met sanitation codes. A Food Manager ordered food for the house. The House President and Vice-President ran the house council meetings. Social Managers planned social events like parties for the house. A few managers with minor responsibilities like gardening and recycling also helped oversee house operations. All managers were student house members and were democratically elected by the other members of the house.7.12

The managers were paid to make sure the house tasks were completed, but it was ultimately the responsibility of all house residents to make sure the house was maintained and ran smoothly. When members did their workshifts, closed doors and windows, followed established rules and held others accountable for following rules, the house to stayed safe and clean. It was also the responsibility of the members to participate in the decision-making processes of the house, i.e. house elections and councils. The system was dependent upon the effort put forth by the membership. The running of the house could break down if most members did not take responsibility for these duties. External agencies like the Central Office, in theory, only interfered with the way a house was run when the entire U.S.C.A. was affected, or when problems were of a drastic nature. All U.S.C.A. houses operated under this system of member control and autonomy, including Barrington Hall.

How Did Barrington Hall Fit In?

Barrington was a house with a dual identity. First, it was a cooperative house within the U.S.C.A. Members signed U.S.C.A. contracts that guaranteed them certain rights such as the right to live in a habitable, safe environment. The contracts also gave to them certain responsibilities, such as cooperating with other members.8.1 But Barrington’s identity extended beyond being a house in the U.S.C.A. In its fifty-year history it built its own traditions, style and reputation. The house was purchased in 1935 and from the beginning was one of the most influential houses in the U.S.C.A.8.2 It was the largest with 195 members. In the span of half a century, the house developed a unique character. Its culture often mocked traditional University culture. For example, in the 50s, members of Barrington entered a float decorated with a giant tower which looked half like Stanford’s clock tower, Hoover Tower (Stanford was the rival of U.C. Berkeley), and half like a penis, entitled “Hoover’s Last Erection” in a University sponsored parade. The float mocked Stanford and the occasion, voicing the mischievous nature of its builders.8.3

As Barrington aged, the tradition of counter culture grew. During the 60s, Barrington served as a breeding ground for radical ideas and students.8.4 In the 70s, Barrington further rejected mainstream culture. On one occasion, to make their stand against the rest of society, some Barringtonians started a campus student club, the Onngh Yanngh Consciousness Society for the Enlightened. The members claimed the club as an apolitical group who refused funding on the principle that they wanted to remain autonomous.8.5 The Barringtonians used this stunt to mock other clubs that took orders from the University, so they could receive funding. Tradition at Barrington of “going against the grain” had become well established.

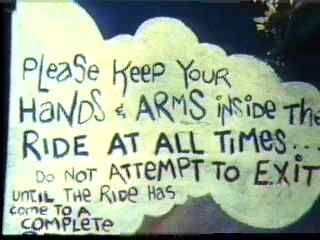

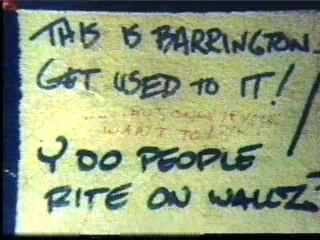

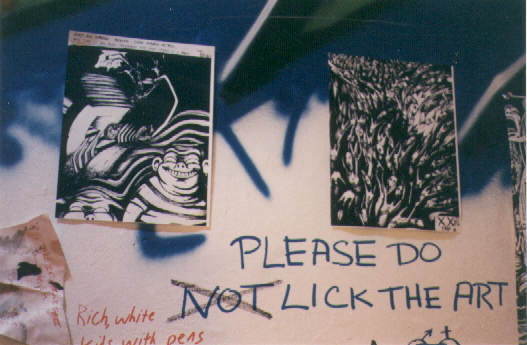

The counter culture that had been built at Barrington took its most extreme form in the 1980s. By then, most of Berkeley’s counter cultural scene had waned. The once radical Berkeley was calming down as the Reagan era set in.8.6 As places in Berkeley where counter culture could thrive went down, Barrington’s role in the counter culture increased. During the early 80s and to varying degrees throughout the decade, the dominant sentiment at Barrington was anti-authority. Most residents took the attitude that they did not want to be told what to do i by anyone but themselves. Freedom was interpreted by them as doing what you want, when you want.8.7 Those who wished to exercise this freedom found a safe haven at Barrington. The freedoms were expressed in forms such as spontaneous graffiti plastered throughout the house, the projecting of objects from the roof, weekend parties attended by five or six hundred people, ands especially, the free use of drugs.

With the non-conventional Barrington attitude came a group of people who were not willing to put forth the effort to maintain the house as a safe, clean environment. Barrington became a place where the homeless, drugs, trashed hallways, and loud people all made a distinguishing mark. With close to two hundred people living in the same building and an attitude, which encouraged them to do whatever they wanted, Barrington was not an environment for all students.

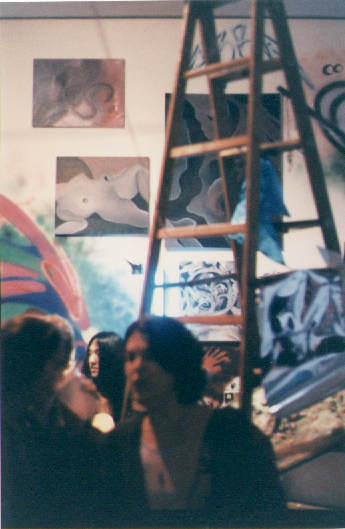

The residents who bought into the counter cultural ideas of the hall found it uniquely beautiful. In a letter to the editor of the Toad Lane Review, the U.S.C.G. newspaper, one Barringtonian expressed his sentiment about the spirit of Barrington. He described the house as “a place of chaos with a sense of order;” “a place for the non-conventional;” and “a counter cultural haven.” From his point of view, Barrington was a place for all types of iconoclasts to live and feel welcome; “hippies, punks, neo-radicals and weirdoes” were all a part of the Barrington culture.8.8 Murals depicting all sorts of creative philosophies splattered the hallway walls. Many residents enjoyed the lifestyle, seeing Barrington as one of the only locations in Berkeley where a wide array of creative, alternatively minded people could freely live and express themselves.8.9 The group that bought into the free loving, let-loose spirit of Barrington i easily perpetuated it. New members, who moved in; were met with the idea that this place is what it is and should be maintained as such.

New Barringtonians fell into several categories. Some residents had previously heard about Barrington and chose to live there to partake in the alternative culture. A majority of residents were new to the U.S.C.A. and moved to Barrington because it was the only house with an open room.8.10A few new residents moved in to discover that they liked the Barrington lifestyle and remained a part of the community. Many new residents put up with Barrington for a semester, and then moved on. They did not like it, but enjoyed the novelty of it.8.11 Others in this group disdained living at Barrington and, at the first chance, moved to a different house. These people found little freedom in Barrington. They locked themselves in their rooms or stayed in other locations to escape the alternative culture. Often they were not yet familiar enough with the democratic process in the co-ops or did not have the time and energy to try to change the house’s ideals. Therefore, the people who loved the house as a counter cultural haven were left with it.

The counterculture was perpetuated by a core group of about fifty residents.8.12 They were the ones who most actively participated in the house. As a united front, these fifty “owned the house.” Often those who enjoyed the lifestyle ran for manager, positions. These managers, wanting to maintain the alternative culture, enforced the rules and passed down the traditions that made this possible. Council members also perpetuated the “freedom at its most” lifestyle. One r Barrington woman went to council seeking a halt to the sexual harassment she had been experiencing from a male resident. After considering the case, the council decided that the male’s right to harass the woman was equal to the woman’s right to be free from harassment, and the two should work out their differences themselves.8.13 Ideally in the co-op system, all members have power and rights. But here, it seems, the ideology of “people doing whatever they want” superceded the rights of all to feel empowered.

This same Barrington attitude was displayed at a city task force meeting attended by neighbors, police officers and Barrington representatives. The non-Barrington community members were complaining about an unacceptably loud party, which had occurred at Barrington. The police had received over 25 complaints and estimated that over 500 people had attended the party. A Barrington representative’s response to the complaint was that if only 25 people complained and over 500 people were attending the party, why should 500 people stop what they were doing for 25 people. He claimed the rights of the 500 partygoers were greater than those of the 25 complainants.8.14 The representative did not even acknowledge that the Barringtonians could have been disrespectful. Some saw their ideology as unquestionably correct.

Barrington residents came from a variety of backgrounds, but often those who bought into the counter culture at Barrington were for the first time without a parent-like authority enforcing the rules. They were indoctrinated in school and their community with new ideas including the philosophies of socialism and anarchy, and being exposed to many new things, including drugs. They saw Barrington as a place they could control, and therefore, a place they could experiment with these new ideas. Many residents saw themselves as carrying on the tradition of the Berkeley counter culture that grew out of the 50s and 60s. They viewed their mission as maintaining the counter culture, despite efforts from the outside world to put it to rest. As it had been in the sixties, they saw Barrington as a place to ignite social action. This desire is seen in practice when, in 1984, residents voted to make Barrington a sanctuary for refugees from El Salvador.8.15

Drugs were a definitive part of the Barrington counter culture. During the late 60s and 70s, more and more college students, including Barringtonians, began experimenting with drugs, especially psychedelics like mushrooms and LSD.8.16 These substances fit well with the antimainstream culture that persisted at Barrington. Students found the co-op to be a welcoming and safe environment to try new things. When in the late 70s and early 80s, hard drugs like heroin and cocaine became fashionable, they also found an open door at Barrington. Drug experimentation became a key component of the Barrington lifestyle. One resident remembers it fondly, “Everyone at Barrington did drugs, or at least tolerated it, or stayed at school and never came to the place. We trippers had won it to ourselves for a few blissful years.”8.17The hall was touted by many residents as a place where drug use was “legal.” They brought their friends and others from the surrounding Berkeley community into the house to buy and use drugs.

Barrington held the reputation among community members as the place to get drugs. Documented as appearing on the wall of a bathroom stall on the U.C. campus was the question “Where does one find hard drugs in this city?” The answer written in large black ink was “Barrington Hall” with accompanying room numbers.8.18 Barrington, every semester, threw several wine dinners and various huge bashes where hundreds of people flooded the dining rooms, hallways and suites, drank alcohol, partook in illegal drugs like LSD and cocaine, listened to very loud punk or rock music and generally partied very hard.8.19 People who never knew Barrington as a student cooperative saw Barrington only as a place where huge parties, outstanding bands and mass quantities of drugs were found. But the drugs brought a seedy element, and under its harmful influence and various others, problems began to arise at Barrington.

What Were the Problems?

Unfortunately, for Barrington, it did not exist in a bubble. Despite all the freedoms they tried to create for themselves, the residents were still connected to the outside world that they were trying to reject. As the 1980s unfolded, hostile forces voiced compelling objections to the Barringtonian lifestyle. They allied with each other to pressure the U.S.C.A. to intervene at Barrington. Insurance companies, neighbors, the Berkeley Health Department, community organizations, the Berkeley City Council, the University, the media and other U.S.C.A. members all pointed accusatory fingers at Barrington. The Barringtonians had taken,principle of autonomy to an extreme, which leaked out into a world that was not willing to put up with it. Tension between Barrington and the outside world eventually resulted in a breakdown.

In 1982, Barrington began experiencing higher turnover rates, lower occupancy, more safety problems, a greater number of sanitation problems and more neighborhood complaints than in previous years. The U.S.C.A. Central Management noticed the new problems and asked the Board of Directors to address them. In the summer of 1982, the U.S.C.A. Board established a committee to look at and brainstorm solutions to these various problems.9.1 The extreme nature of the counter culture at Barrington had not yet become apparent to the U.S.C.A., and after surveying members and discussing the issue, the Barrington Committee, as they called themselves, decided that the root of Barrington’s many problems lay in the physical configuration of the hall. In drafting solutions to the problems, they focused mainly on what should be physically changed about the building. The committee thought that if residents moved into a Barrington that was in optimal physical condition, they would have more of an incentive to take responsibility for keeping the house in top condition. For example, they hoped that a reorganization of the kitchen would make more efficient use of the area, and members might be more inclined to take care of it. The committee also viewed the house as not having enough common space. Seeing this as a problem that led residents to move to houses that offered more common space, they opted to convert some suites into study rooms. The problem of a large number of non-residents coming in and out of Barrington was addressed by moving the front door from the highly trafficked Dwight Way side of the house to the less frequented Haste Street side. They also desired to paint over some of the graffitied murals that gave the hall an unappealing appearance. These changes, thought the committee, would improve some of the problems Barrington faced.9.2

While the plan for the physical restructuring of Barrington was in the discussion process, outside influences also began to voice concerns. In January 1983, Barrington’s insurance coverage was cancelled due mainly to what the insurance company saw as safety problems. The insurance company was investigating the building to address a lawsuit that was filed against the U.S.C.A. by a former Barrington resident who had fallen down an airshaft in 1981. The safety problems seen by the insurance company included major maintenance problems such as broken doors and stair railing, general housekeeping issues such as trash piled in hallways, as well as the premise’s overall appearance. Another element cited as a safety issue by the insurance company was the constant presence of transients roaming in and around Barrington. These street people and other “undesirables” were seen as associated with drugs, violence, and theft at Barrington. According to the insurance company, residents could not feel personally safe or feel that their possessions were safe with such a large non-resident population in the house.9.3

Of course these problems were not unique to Barrington. Many co-op houses, especially the large ones, experienced similar problems.9.4 But the cancellation of Barrington’s insurance did wave a red flag in the face of the U.S.C.A. Board. The U.S.C.A. could not afford to operate Barrington without insurance, and the cancelled insurance of this house threatened the stability of the entire organization’s insurance. Immediate efforts at the central and house levels were instigated to resolve the safety issues. A Central Level maintenance crew helped the Barringtonians fix the broken doors and stair railing, and the house focused more workshift power on cleaning. For the long-term future of Barrington, members of the Board saw three possibilities. First, they could close the building for the spring and summer quarters for repairs, an option that would result in the displacement of many spring residents and a few summer ones. Second, they could increase the rent at Barrington by charging the residents for the higher insurance rates, the likely result of buying insurance from a different company. The rent at Barrington was less than the rent at other U.S.C.A. houses to encourage more students to choose to live at Barrington. This second option reduced the rent differential decreasing the incentive to live in the house. Finally, the Board had the option of hiring an outside agency to help clean up Barrington and charging the costs to the residents, implying that perhaps the current residents were not apt to tackle the problems themselves.9.5

That spring, despite Barrington’s passing a follow-up insurance inspection, the Board voted to close and renovate the hall for the summer. More committee meetings and several surveys of Barrington residents further illuminated what should be improved at Barrington. Security, general dirtiness, and maintenance issues again topped the list.9.6

The summer of 1983 saw the beginning of construction at Barrington. The Board hoped to have the hall freshly rehabilitated by the following fall. But when fall rolled around, the project was not complete, and residents were forced to move into a noisy, dusty construction zone with unpainted walls.9.7Residents grumbled as construction continued into the semester. The problems caused by poor planning for the renovations made things worse for Barrington. Members, having moved into an unfinished Barrington, felt their suggestions unheeded by the U.S.C.A. and angrily demanded that their desires be met. The renovations had included painting many of the walls white, thus removing the murals and graffiti that were a source of pride to some residents. The residents saw the renovation as “fixing” non-problem areas instead of replacing what really needed to be fixed. Some old members threatened to trash Barrington if the U.S.C.A. did not make further efforts to renovate the building. Seeing the Barrington threat as uncooperative and destructive, the Board responded with its own threat to kick out any members who acted destructively.9.8 An unusual amount of tension began developing between Barrington and the Board.

Barrington’s situation was further complicated when, at the end of 1983, its neighbors filed a complaint with the city of Berkeley, accusing the house of being a public nuisance. There is no doubt that many neighbors hated Barrington. They were the non-co-op group most directly affected by “the Barringtonian lifestyle.” The neighbors complained that filth, unruliness, drug activity and noise at Barrington plagued them.9.9 The outside walls of Barrington were covered with unsightly graffiti. The spray painted words read “terrorist” and “this is Barrington, get used to it.”9.10On the sidewalk in twenty-foot tall letters, appeared “LSD,” an obvious indication of drug use according to neighbors.9.11 When the dumpsters were filled with trash, claimed the neighbors, the excess was left to spill over their sides. Noise from a stereo in the downstairs kitchen was reported by them to leak constantly in through the windows of surrounding apartments. Many of the older neighbors (not college students) were disturbed by the huge parties, several every month, which lasted well into the morning hours. Barrington had the reputation among neighbors as a den of drug activity, which attracted “undesirables.” One neighbor described Barrington as “a noisy, unsafe, unsanitary, rat trap.”9.12 Complaints piled high on city officials’ desks. The neighbors had most likely been irritated by Barrington for many years. Their frustrations compounded as the unruly Barringtonian behavior grew worse.

Under these circumstance, when, in 1983, one of Barrington’s neighbors, the Ellsmere Apartments, filed suit with the City of Berkeley’s district attorney in an attempt to shut Barrington down, the city and the U.S.C.A. took the matter seriously. In January 1984, in response to the suit, the City set up an arbitration committee, the Joint Tenants’ Council, made up of three Barringtonians, three residents of the Ellsmere Apartments, the U.S.C.A. General Manager, and the U.S.C.A. president, to handle the problem.9.13 The Council met several times and arrived at a set of guidelines for how Barrington and the Ellsmere Apartments should interact. Barrington agreed to follow some new rules. First, a restriction on parties to one per month, which were to end at 2 A.M. and be kept completely indoors, was instituted. The radio that blasted music from the Barrington kitchen windows was to be played only within a range farther than 30 feet from closed windows. The Barrington managers were asked to wear pagers so that Ellsmere residents could contact them at all times. The restrictions were agreed to by Barrington with the promise that Ellsmere would drop the suit against them and show more tolerance toward the Barrington lifestyle. A five- member Barrington action group was created to oversee the enforcement of the agreement.9.14

Opinions over the Ellsmere-Barrington agreement differed among co-opers. One U.S.C.A. news writer from the generally conservative Hoyt Hall saw the restrictions as unfair. She did not think so much control over Barrington should be given to an outside group such as Ellsmere.9.15 But others thought that Barrington needed to clean up its act and saw this neighbor complaint as an opportunity to lay down some ground rules for the house.9.16

Unfortunately in practice the Barringtonians saw no need for ground rules. The agreement was essentially ignored from the day it was signed.9.17 House members soon forgot or ignored the agreement and continued to act in an unruly fashion. The neighbors continued to complain. The problems with its neighbors plagued Barrington to its end.

In February 1984, during the troubles with the Ellsmere apartments, and most likely because of them, the Barringtonians were hit with a surprise city health inspection which they failed miserably. The inspectors threatened to shut the kitchen down if a six-page list of violations was not corrected.9.18 Again the U.S.C.A. intervened to help Barrington clean up. But the failed inspection made the already scrutinized Barringtonians more hostile toward the outside world. The House Manager felt the Barrington lifestyle had been disrespected by the Health Board. Other houses had kitchen sanitation problems, but Barringtonians thought they were singled out by the inspectors. The House Manager claimed that the health inspectors “said not enough people were using the serving utensils. When people came down the stairs to eat, they said it looked like they hadn’t washed their hands.”9.19 Such charges were seen as direct insults to Barringtonians. Still Barrington was forced to comply with the city’s demands so they could retain a food service license. The hours of workshift owed were raised to six per week, more than any other U.S.C.A. house. Barrington also organized a massive house-cleaning party to meet the demands. But the damage had already been done. Barrington was put on a one-year probation under the terms that with one failed kitchen inspection, the house’s food service license would be suspended and with two failed inspections, the license would be revoked.9.20 The U.S.C.A. could not afford to operate its largest residence hall without food service; too many people would cancel their contracts. The probation placed the heavy burden of being constantly under the watch of city officials and the central U.S.C.A. management on Barrington, especially its managers. This stress did not improve existent tensions between Barrington and the rest of the world.

The Summer of 1985, later dubbed “Hell Summer,” brought the U.S.C.A. to the realization that a very serious situation was at hand in Barrington. The house was running at a reduced capacity of 40-50 residents for the summer. Each resident held a suite with a bathroom and several bedrooms. Many of the residents illegally rented out the extra rooms in their suites to transient students and others. By mid-summer, it was clear that around 125 people were living in Barrington, whereas only about fifty were legal tenants.9.21 With such a large number of nonresidents in the house, general anarchy reigned. There was no accountability, financial or otherwise, of the non-residents for the house. They consumed drugs and alcohol, made uncontrolled amounts of noise, left the house unkempt and generally ran amuck.9.22 The U.S.C.A. took action to kick those subletting out, which was difficult because the organization did no want to infringe on members’ privacy by entering their rooms without permission. By the end of the summer, Barrington had been trashed by the summer residents and their illegal guests. The U.S.C.A. could do nothing to recover debts for the damage done by the people illegally subletting and very little to punish the residents.9.23 “Hell Summer” further enforced the “do want you want” attitude at Barrington.

In the fall of 1985, rumors of drug abuse in Barrington spread. A sensational Oakland Tribune expose on the co-op house accused Barrington of harboring a large number of resident and visitor drug users.9.24 In the rather conservative, anti-drug era of the eighties, this newspaper article, widely read by community members, created shock waves for the U.S.C.A. The Berkeley City Council expressed grave concern for Barrington, as did the U.S.C.A.’s insurance company. The waves brought by the article were calmed by the central U.S.C.A. management. The organization’s response, “kids will be kids,” implied that the average college student in the mid-1980s, be they in dorms, fraternities, sororities or apartments’ experimented with some drugs. Barrington, they claimed, was no different. The U.S.C.A. gave the impression that the situation was under control. That impression did not last for long.9.25

As the problems at Barrington were further illuminated, the U.S.C.A. Board felt the need to take action. The situation was discussed at the September 19th Board meeting. The U.S.C.A. General Manager recommended that Barrington be closed and cleaned thoroughly during the summer of 1986. He also recommended that the current house membership be moved to different houses, no house having a membership of more than 10 percent of ex-Barringtonians.9.26 This proposed action had occurred in the early seventies at the 28 person Euclid Hall when a few anarchistically minded managers took control of the house and behaved uncooperatively, painting all the walls black, and generally making life hell for the rest of the residents.”9.27 The arguments cited for such a drastic action at Barrington were the same arguments used two years earlier when problems at Barrington were first discussed. Previous actions seemed to have changed nothing. Member injuries and lawsuits, insurance hassles, costly renovations with disappointing results, poor neighbor relations, City Health Department violations, difficulty filling the hall to capacity, AdCom cancellations, and most importantly, Barrington’s failure to reverse itself in the areas of noise, sanitation, drugs and allowing minors to crash there were all concerns that contributed to the Boards discussion.9.28

A group known as PACT, “Parents and Children Together,” a pro-family community group, also appeared at the Board meeting to voice their grievances with Barrington. They presented several stories about teenagers who ran away from home and found a refuge with sex and drugs at Barrington. One woman even claimed that her daughter had become a prostitute there. PACT asserted that a place like Barrington should not be allowed to operate within a community. They wanted immediate action to be taken by the Board to deal with Barrington. Barrington management denied that runaways were currently being given refuge there, although, they could not account for the past.9.29 Given the attitude that pervaded there the previous summer, the accusations were most likely, at least partially, true. Barrington could not deny that these problems had existed in the house. The Board, under pressure from PACT, the Oakland Tribune and their general manager, voted to create another Barrington Action Committee to assess Barrington’s problems and its future. They were not yet ready to exercise direct authority to control the house.

Barrington management viewed the complaints of the Board and the Central Level staff as unwarranted. They felt they had not yet been given a fair chance to show that Barrington was improving. To increase satisfaction with Barrington, they suggested that the house’s lifestyle be advertised by the U.S.C.A., so it would attract a group more willing to adapt to it. They seemed to want to change their reputation without changing their culture. One Barrington manager noted that there was a difference between changing the bad points about Barrington and changing the lifestyle. The house president said that the Board’s efforts would “not infringe on the character of Barrington,” indicating the strong loyalty to maintaining the current Barrington philosophy.9.30 Unfortunately, some of the bad points at Barrington were perpetuated by the alternative lifestyle. In this case, the sentiment of the house was in direct conflict with attempts to improve the house.

Later that semester, the San Francisco Chronicle published an article, which again proclaimed that Barrington had a serious drug problem, only this time heroin was specifically cited as being the main drug involved.9.31 After this article, the U.S.C.A. could not relieve public concern. The U.S.C.A.’s insurance company now cancelled the insurance for the entire co-op, putting the organization in at risk. In response to the article, the Berkeley City Council asked the district attorney to look into the drug situation at Barrington. A City Council subcommittee was formed, and the U.S.C.A. formed its own investigative committee. The U.S.C.A. now had two committees investigating Barrington. The results of the U.S.C.A. investigation yielded that there was indeed a heroin problem at Barrington. Drug use was found to be more rampant than originally thought. The organization held a poorly attended press conference to convey their discovery and assure concerned community members that something would be done to curb the problem.9.32 Community members responded with accusations that the U.S.C.A. was unfit to handle its problems.

Early spring 1986 saw a frantic situation at Barrington. Both the U.S.C.A. and the City of Berkeley were looking into what was happening at the house. The attention placed stress on the members who were making strong efforts to keep the house clean, cooperate with neighbors, improve security, and deal with excessive noise and drugs. A core group of Barringtonians devoted themselves to improving the image of the house. They added new locks to the doors, painted murals over graffiti, and had one street person who was staying in the house arrested to deter non-residents from living in Barrington for an extended period of time. But their efforts were mocked by other house members. New graffiti appeared soon after the old had been painted over.9.33 The anarchistic, countercultural lifestyle was still heralded by many members. The destructive influence of a few was enough to strain the efforts made by concerned members. Even those concerned with improving Barrington continued to endorse the old lifestyle. The attitude of change only penetrated skin deep. At heart the Barringtonians were the same.

After some investigation, the U.S.C.A. determined that dozens of habitual heroin users and dealers lived in Barrington, and many students there said that they had tried heroin at least once.9.34 This worried the U.S.C.A. staff and the city officials. The U.S.C.A. called in resources from the University, the City of Berkeley, and some local drug treatment programs to deal with the Barrington drug problem. Half a dozen in-house heroin dealers were evicted but non-residents continued to be a part of the Barrington scene bringing drugs and the desire to use drugs.9.35 In late February, the papers publicized an article about an Oakland man who was hospitalized after a heroin overdose at Barrington.9.36 More accusations of drug abuse followed. Three other drug overdoses were reported that semester. Despite the U.S.C.A.’s efforts to combat the drug problem, it continued.

Responsibility to keep drugs and unwanted people out of Barrington ultimately belonged to the residents. Central U.S.C.A. Management could not control all members. Only the residents themselves could change Barrington’s habits. As long as apathy or acceptance of drugs was the dominant attitude, the problems would continue. The residents were the people who could everyday enforce the rules and policies. If they did not recognize Barrington’s problems, there would be no way for the U.S.C.A. to find solutions for Barrington.

The U.S.C.A. President called an emergency Board meeting to discuss the U.S.C.A.’s plan of action for Barrington. Heroin overdoses of non-residents had been reported. Vacancy rates were higher than they had been for years. Bad publicity for the U.S.C.A. was rampant. Barrington’s members continued to blame the current situation on the “general anarchy” that prevailed the previous summer and asserted that the house was regaining control. They insisted that the reputation of Barrington’s problems far exceeded its actual problems and begged the Board to allow them to deal with their problems themselves, as a community.9.37 But the Board, in its own effort to regain control, voted to close Barrington indefinitely.

The situation was a hot topic among co-opers. Some U.S.C.A. members saw Barrington as a vital part of the U.S.C.A. and thought it was being scapegoated by a media that reacted with hostility toward any alternative lifestyle. Others thought the house should be dissolved. They claimed it was an unpleasant place for new co-op members, yet the only place for a new co-oper to secure housing. Barrington Hall, some members complained, was draining U.S.C.A. funds. Barrington managers argued that with enough energy the house could improve its reputation among community members, but still saw no reason for the house to sacrifice its acceptance of alternative lifestyles.9.38

In April 1986, Barrington members circulated a petition among U.S.C.A. members calling for a member referendum, a vote of all U.S.C.A. members, to keep Barrington Hall open. A plan for probation was included in the referendum. Under the probation plan, all major managerial positions were placed under the direct supervision of the Central Level, the right was given to the Central Level to require residents to sign an additional conditional contract, Central Level office hours were to be held at the house, the residential capacity for the house was reduced, and the police were given keys to house common areas, so they could make rounds regularly.9.39 No previous co-op house had been placed under so much Central Level or police control and scrutiny. But this level of supervision was the only way Barringtonians saw they could keep their house alive. In their opinions, any Barrington was better than no Barrington. All 139 Barringtonians who voted in the referendum chose to keep the house open. Some did not want to be kicked out of their residence. Others felt strongly that countercultural and artistic ideas needed a place like Barrington to thrive. By a vote of 565-419, U.S.C.A. members voiced their desire to keep Barrington open under the conditions of the probation. Even if Barrington had not voted, a slight majority of the other voting USCG members wanted to keep the house open by a vote of 426-419.9.40

But, as can be seen, U.S.C.A. opinion about Barrington was split equally. Some co-op members, especially those who lived in small houses, saw Barrington as a blemish to the U.S.C.A. They thought the idea of keeping it open in its present state was ridiculous. Some had been former Barrington members who moved out to escape the problems and lifestyle. This group claimed to know, firsthand, the problems with the counterculture at Barrington.9.41 Still others who had once lived at Barrington remained loyal to the house. Even though they no longer chose to live at Barrington, they thought Barrington should remain open as a place to be experienced.9.42 Many U.S.C.A. members in favor of the referendum lived in the bigger U.S.C.A. houses and sympathized with Barrington’s plight. Large houses like Cloyne also experienced problems like those at Barrington. Noise complaints, sanitation issues and drug problems were found to a lesser degree at these houses.9.43 The members felt the Barrington culture was not extremely different from any other co-op living situation with a large number of people.

Barrington was closed for the summer of 1986, but opened again in the fall under the supervision of a full-time, professional, hired manager. Carlos Cabana, a man in his early 20s from Cloyne, took on the position of first professional manager of Barrington.9.44 He managed there for one year and ran the house in conjunction with the “B Team,” the Barrington team, a group of Central Level managers and staff, also known as the Central Level Management Team. The “B Team” regularly met with the Barrington managers to make sure the house was running smoothly. The “B team” was seen by some as controlling and oppressive, against the co-op principles of democratic member control and autonomy, so about six student Board members joined to form a Barrington response task force and wore pagers. If a problem was reported at Barrington, the Board task force responded to it.9.45Cabana, the “B Team,” and the Board task force managed to keep a loose lid on Barrington for twelve months. They were not able to change the counter cultural persona of Barrington, but did keep it fairly subdued. During Cabana’s management, the Barrington controversy did die down a bit, but problems continued as the neighbors persisted in their accusations against the hall and now against the U.S.C.A. as a whole.

In February 1987, one neighbor, John Harmon, raised controversy in the press when he accused the Central Level Management of the U.S.C.A., particularly General Manager George Proper, of negligence in dealing with drug problems at the house. Harmon claimed that Proper knew the extent of the problems at Barrington but did nothing about them. Proper’s inaction, according to Harmon, had endangered the lives of the students of Barrington. Harmon cited the example of Bill Crooks, a drug dealer with AIDS who formerly hung around Barrington and who indicated on a television news show that he shared needles with at least three Barringtonians. Harmon also claimed that Barrington members and U.S.C.A. managers took a code of silence to cover up the drug activity at the house.9.46 He claimed Barrington’s Onngh Yanngh symbol and motto were proof of the code of silence. The Onngh Yanngh symbol, a “Y” with an “O” in its crux, was used by Barringtonians to symbolize the spirit of Barrington. It was accompanied by the motto, “Those who know don’t tell. Those who tell, don’t know.” It originally was published in a Barrington Hall newsletter as a joke, but was later converted by Barringtonians into their symbol.9.47 When Harmon began accusing the house of having a “code of silence” evidenced by the Onngh Yanngh symbol, house members found humor in pretending that the accusations were true. As viewed by the Barringtonians, Proper, and many others in the U.S.C.A., Harmon’s claim was ridiculous. Harmon, they said, was a man determined to shut Barrington down by any means, including making sensational accusations in the press.9.48 Harmon fought Barrington for many years, drawing other neighbors into his crusade along the way.

By the end of his management term at Barrington, Cabana had adapted to the Barrington climate and became a member of the Barrington community. So when Robert Dick, an ex-Barringtonian, was hired as the next manager of Barrington, it was not surprising that he too was "one of them". As a former member, Dick understood and was sympathetic to the Barrington culture. He kept an even looser lid on the house than Cabana, showing more leniency in enforcing probation policies.9.49 In September of 1987, Barrington threw a wine dinner at which a bowl of punch laced with LSD was served freely to party attendees. Several people were hospitalized after consuming the punch, one with spinal injuries after jumping off the three-story roof of a neighboring building.9.50 Always looking for another scandal, the news media picked up on the story. Community members, including the City Council and University officials, were again alerted to a drug-related incident at Barrington. They pressured the U.S.C.A. to do more.

The City Council gave a variety of reactions. One City Councilwoman, Shirley Dean, now proclaimed that the U.S.C.A. could not handle Barrington and the University should take control of the management at Barrington and run it as a student dormitory. This solution would have stripped Barrington of its student-owned, student-run status. With her demand, she did not seem to realize how important democratic control of the co-op was to the students. She seemed to only see Barrington as a political symbol, an example to other groups that illegal behavior would not be tolerated. The University did not seriously consider her demand.9.51 Another Councilman, Don Jelenik, announced plans to create a committee to investigate the charges. He thought the City Council should have more than just media reports before condemning the place.9.52 Other council members saw Dean and Jelenik as overreacting. Councilwoman Nancy Skinner said, “Drug use is an endemic problem of student life regardless of whether you live in the dorms, the co-ops, or the Greek system. I don’t condone the situation at Barrington Hall, but we have to realize that this is a student wide phenomenon and I don’t see why the city should get involved in the affairs of the U.S.C.A. any more than it should in that of the frats or the dorms.”9.53

The University’s Dean of Students, Don Billingsley, also responded to the situation. He sent a letter to Proper urging the U.S.C.A. to act definitively to prevent such incidents from occurring in the future, threatening to remove all University recommendations of the U.S.C.A. as a viable housing option if effective measures were not taken.9.54

Neighbors also used the incident to condemn Barrington and the U.S.C.A. Neighbor Beverly Potter, a woman with a PhDin organizational management psychology, wrote a scathing letter to Councilman Jelenik, accusing the U.S.C.A. of being a “slum lord” and taking intentional actions to “cover up” the scandal at Barrington. She asserted that the U.S.C.A. was unfit to exist in the Berkeley community, blaming poor central management for the out-of-control nature of Barrington.9.55 She later filed a suit against the U.S.C.A. for such charges. Barrington’s countercultural lifestyle seriously threatened the U.S.C.A.

In October another Board meeting was called to discuss the situation at Barrington. As expected Councilpersons Dean and Jelnik, Barrington neighbors, and some members of the press attended. The presence of so many community members at the meeting placed a heavy pressure on the Board to act. Some Board members argued that the U.S.C.A., as an autonomous organization, should not give into the outside pressure. But all Board members knew the top had been blown; something needed to be done.

The incident raised questions about the effectiveness of an outside manager at Barrington. There were misunderstandings about who was responsible for the incidents. Was the incident the fault of a few out of control members who spiked the punch or poor management? At the meeting, the Board urged Robert Dick to resign as Barrington’s manager. It was difficult for Dick alone to control the actions of over 150 people. He heeded their request and his duties were assigned to the Barrington house president.9.56

More questions were raised as to whether the acid punch was an isolated incident or whether little had changed since the Barrington probation. Gene Jun, the house manager in the fall 1985 semester, claimed the house had changed. Previously the members had been “oblivious,” taking the attitude of “no one can touch us.” But now the “open community is gone. Barrington no longer takes pride in a lack of guest policy, an attitude which left doors open to crashers, and eventually drew in street people and dealers.” The current kitchen manager at Barrington claimed that the prevailing attitude was “it’s not cool to do heroin anymore.”9.57 However subdued members claimed Barrington had become, some members still had the impression that “anything goes" and acted accordingly. These members and toleration of them by the rest of the house contributed to further distrust of Barrington. Under pressure from the City Council, University officials, the insurance company, and members of the press, the Board, at a November meeting, voted once again to shut the house down and reopen it the next fall with one hundred percent turnover. According to the Board, Barrington had picked the wrong time to publicly break the rules.

As previously, Barringtonians joined together to push for yet another co-op-wide referendum to replace the Board decision for closure and 100 percent turnover. They argued that the issue was of such importance that it should be considered by all members. The Barringtonian opinion was that “the status quo is a viable solution to all the house’s problems,” given enough time. Barringtonians pointed to the evidence that directly after the wine dinner, even before pressure had been applied by the press, actions like the council’s banning of wine dinners for the rest of the semester, increasing in-house security, and working out a better management structure were taken. The Barrington ians had; since the Board meeting, invited Councilman Jelenik to meet with the house. According to house management, he expressed feelings that he had previously been misinformed by the media and others about the problems at Barrington. He too thought reports had been greatly exaggerated. Signatures of the needed 15 percent of the U.S.C.A. membership were collected, and Barrington was granted its referendum.9.58 Again the Board decision to close Barrington was overturned by the membership, allowing the house to continue operations under the supervision of a hired manager and the Central Level Management Team. Despite all the hoopla about the "acid punch" incident, it was put to rest rather quickly. But by now the patience of the U.S.C.A. and the community ebbed.

Early in 1988, two Barrington neighbors, Sebastian Orfali and Beverly Potter, filed a lawsuit in the state court accusing Barrington of being a nuisance to neighbors, thereby reducing the property values of neighboring buildings. The suit also accused the Barrington members and the Central Office employees of intentionally causing the neighbors distress, and indicted the organization with racketeering charges. They accused the U.S.C.A. of carrying out activities, which included interstate drug trafficking.9.59 The neighbors claimed that the Onngh Yanngh symbol and motto as evidence of the “code of silence” taken by Barrington and U.S.C.A. managers to hide their drug operations: “Those who know don’t tell.”9.60 The press loved this story, and the neighbor’s lawyer, Donald Driscoll, leaked any information he came across, substantiated or not, to it. Presumably, he hoped to bring as much evidence forward in the case as possible. In this attempt, Driscoll was successful; two other lawsuits were filed by him in the names of Charles Spinoza and Ruth Oscar, Barrington neighbors.

The Orfali-Potter lawsuit gave the U.S.C.A. reason to worry for the plaintiffs were asking for $1.5 million. As the case proceeded, the U.S.C.A. concluded that the individual rights of some members and staff were in danger. The organization hired a well-known civil rights attorney, Ephraim Margolin, to defend it.9.61 The new attorney came with a high price tag, and the U.S.C.A. Board voted to raise member rents $40 and mortgage Hoyt Hall to pay him.9.62 The financial burden of the lawsuit was a source of contention among members as it carried on for several years in appeals courts. Worries about it played a major role in their later to shut Barrington down.

The 1988-1989 school year saw some improvement at Barrington and little in the way of new controversy, offering some relief to the U.S.C.A. and the house. But in September of 1989, two years following the first scandalous acid distribution incident at Barrington, reports were made to the Central Level Management Team of a second party at which acid was freely distributed, this time by major house managers. The report also alleged that house funds were used to purchase nitrous oxide. A few people claimed that acid distribution at Barrington was a common occurrence, a tradition, but was usually easily hidden by in-house Barrington managers. This allegation had no substantial proof, but from the stories people recall about Barrington today, it seems likely that the allegation had some validity. To discuss all allegations, the Barrington House Council convened in an emergency meeting. The report given to the Central Level by the House President indicated that the council found allegations of manager involvement to be false. The council concluded that the people suspected of “informing” the C.L.M.T. held hostile feelings toward the house because one of them had been kicked out. Another non-managerial Barrington member asserted that most house members had little, if any information about the incident. It seemed to her that the house managers were trying to keep a tight lid on the incident even among house members.9.63 There seemed to by a discrepancy between what house managers and some members were saying.

The next week, the Board convened to discuss drugs at Barrington for a third time. To sort through all the contending stories, they established an investigative committee. Having learned from past mistakes, the Board also sent out a press release to curb any media controversy. It stated, “The U.S.C.A. does not condone and will not tolerate any illicit drug activities in our homes. [If the incident is true] drastic and permanent action for change at Barrington Hall [will be taken].” They realized the need to warn Barrington and hoped the statement would relay the message that the U.S.C.A. would no longer put up with the house’s antics. A copy of the message was slipped under every door at Barrington. The Board also hoped the statement would deter Donald Driscoll from using the incident as evidence in his lawsuit.9.64

This time, a few non-Barrington Board members circulated a petition calling for a member-wide referendum on the issue of whether or not to close Barrington until a better use for the building could be found. Scott Fitz, a representative of Stebbins Hall, lead the fight to close Barrington. In an editorial in the Toad Lane Review, he wrote that “Barrington Hall as it currently exists is not a functional part of the U.S.C.A. Barrington has resisted attempts to solve the problems for years.” Fitz cited continued kitchen inspection violations, evidence of illegal subletting, and officials covering up the distribution of acid as reasons for closing the hall. “Even though they love their house, they cannot solve its problems,” he said. “The U.S.C.A. has a responsibility to Barrington members who cancelled their contracts, future members and current members to recognize Barrington as a failure.”9.65 A current manager of Barrington agreed with Fitz, referring to an attitude of denial at the hall. The members, he said, were drilled with the idea that it is the rest of the U.S.C.A. that is losing its values, not Barrington. With this attitude, he thought, Barrington could never change.9.66 The Orfali-Potter lawsuit was using U.S.C.A. resources in the courts, and Barrington opponents argued that a definitive action to stop the problems at Barrington would help the U.S.C.A. contest the suit. Giving Barrington yet another chance, it was argued, would only provide the prosecution with more evidence of ineffective U.S.C.A. management. The lawsuit argument was reported to have strongly influenced those who chose to close Barrington.9.67

In the same issue of the Toad Lane Review, Evan Steele, President of the U.S.C.A. during the first acid distribution incident and, ex-Barringtonian, argued for the continued existence of Barrington. Steele asserted that the financial impact of closing Barrington for the U.S.C.A. would be tremendous, hundreds of student beds would be lost. He cited the city health inspector as calling the Barrington kitchens “the cleanest in the co-ops.” He blamed vacancies on the reputation perpetuated by persecution from the city and the press. The problems, according to Steele, were much different From those of the past. He wrote, “I believe that we should only let outside pressure dictate our actions in times of severe crisis and pressure, and I don’t see that environment in the present, or for years.” He urged the U.S.C.A. to “not give into mainstream culture which threatens the lifestyle of individuals or societal forces hostile to progressive movements, individual freedoms or any form of dissent. We must defend Barrington’s lifestyle as inexorably connected to our own.” He implored the U.S.C.A. Board to work with Barrington to instigate change internally, rather than creating a hostile duality of us versus them.9.68

But the U.S.C.A. membership must have tired of hearing Barrington’s pleas. The referendum to close Barrington for the spring 1990 semester passed. The members directed the U.S.C.A. to close Barrington for one year, while it was refurbished, so it could reopen with a new group of residents, none of whom had resided in the building. FallCom, a name that ironically predicted the eventual fate of Barrington, discussed possibilities for the building.9.69

With their sentence imposed, many Barringtonians felt betrayed. Some released their frustrations by plaguing neighbors. They threw paint from the Barrington roof onto the skylights of the neighboring apartments and also threw a washer and dryer off the roof.9.70 But their time was up, their boost was gone. Or so the U.S.C.A. thought.

All but seventeen Barrington residents moved out in the spring of 1988. Those seventeen men and women protested the closure by staying as legal “holdovers” in the building. The U.S.C.A. issued member contracts for an entire school year, iėboth fall and spring semesters. When the U.S.C.A. membership opted to shut Barrington down before the spring semester started, they cancelled the residents’ contracts. But legally the residents could contest the cancellation and in the meantime, could stay in the building until they had been formally evicted. These seventeen members chose to exercise their squatters while they appealed eviction.9.71

For the first few weeks of the “holdovers” stay in the house, they “partied like there was no tomorrow.” (There was no tomorrow.) The seventeen Barringtonians threw massive, loud 500-person parties every weekend. They methodically destroyed the house. Their vandalism was dramatic and well planned. On one instance, the Barringtonians climbed onto the roof, ran a fire hose down a light shaft that provided air circulation to a column of bathrooms, and turned it on with the intention of flooding and destroying the dining room and the rest of the house.9.72 The large amount of damage from that incident was only a fraction of what they had done by the time they were evicted.

The “holdovers” seemed to be claiming the house as theirs; they did whatever they wanted to it to express this attitude. Their actions demonstrated anarchy at its most extreme. The “holdovers” actually thought that they would win the eviction appeal and Barrington would continue as their counter cultural haven.9.73 A few non-”holdover” ex-Barringtonians were organizing to independently purchase the house from the U.S.C.A.9.74 The Barrington members felt a strong commitment to their house, most assuredly multiplied by the drive to kick them out. They truly thought they had a right to live as they wanted in Barrington.

The U.S.C.A. hired security guards in an attempt to secure the building. At first entry level Brink’s Security Guards were called in. But with larger scale vandalism of the house, Phoenix security guards who carried firearms appeared.9.75 The situation of the house held hostage was intense for all involved.

One Friday night in March, three months into the standoff, George Proper received a phone call from the security guards asking if they could allow the holdover Barringtonians to have a small, quiet poetry reading. Proper told the security guards they could allow the poetry reading to take place. At six in the evening, all was calm at Barrington. But by eight o’clock, Proper received a phone call telling him to get over to Barrington, since the poetry reading was out of control. As he drove cast on Dwight Way, he saw police cars lining the streets for several blocks. He stepped out of his car and noise from the amplified music almost knocked him down. The police were lined up in front Barrington in riot gear waiting to pounce.

For an hour, Proper tried to negotiate with the partiers. As he walked down the house’s halls, people ran through them screaming and yelling. When he asked them to shut the party down they would continue yelling or spit at him. The mood was chaotic. The police presented Proper with the ultimatum of shutting the party down now or leaving and not returning. Proper directed them to shut it down.

In the dining room, the police formed a riot line at one end of the room and the hundred or so party goers stood at the other end-of-the room. Proper and Neil Huston, the U.S.C.A. physical plant manager, stood behind the police line. The confrontation stirred the energies of the Barringtonians. They began to chant, “we want George, give us George,” and threw beer bottles in the general direction of Proper, not trying to hit him, he later claimed, but making the statement that they would not give in to the authority of the police. The police started moving in unison toward the partygoers and as they got closer, the partiers panicked and ran out of the dining room into the rest of the house.9.76 By this time, the entire southside area of Berkeley had heard that there was a riot at Barrington, and many people rushed over to watch or take part. The police had not secured the rest of the house, so approximately 350 people stormed the building, running through the hallways and breaking anything they could. Outside on the Dana Street side of the building, the residents and rioters began a giant bonfire fueled by Barrington’s furniture, which they had thrown down from the roof. The fire department arrived at the scene to put out the fire. But the rioters picked up the bottles that had been left by neighboring residents for recycling as well as bricks from a chimney that had been damaged during the earthquake of the previous year and hurled them at the firefighters and police.9.77 A fireman and a policeman were hit with bottles and bricks. and the situation was deemed to be out of control. The riot squad was called in to evacuate the building. By that time the police were very frustrated with the rioters, and as they cleared out the building, they bashed in computer screens and used hostile force.

Some evacuated residents later claimed that the police treated them brutally, beating females and minorities excessively. The rioters were not allowed back into the building until the next day.9.78

The riot brought out the intense emotions that had been building all semester. Residents thought of the incident as an example of the oppressive nature of the U.S.C.A. They equated the police brutality against residents with the “brutal” way they were stripped of their home.9.79

The riot left the “holdovers” charged with destructive energy, however, their moods soon changed when one of them died. The sealed door to the roof could not be opened by residents, so they had been climbing out a window, up a gutter pipe and reaching across a two- to three- foot overhang to pull themselves on to it. One day while trying to climb onto the Barrington roof, a “holdover” fell and died. His death brought a somber mood to the rest of the “holdovers.” Other factors also worked igiinst them. Later that week, the group lost their final court appeal to stay in the house, and the eviction was set. On a Thursday night, it was leaked to the residents that the sheriff would appear to evict them the following Monday. But the U.S.C.A. with the sheriff showed up by surprise on the next morning, Friday, to carry out the evictions. The “holdovers” had not prepared for the eviction by calling in help to hold down the house and were already drained by the recent death. They did not protest when the sheriff arrived. They had been defeated. The hall’s doors were sealed with plywood.9.80

Tragically, the damage clone by the holdovers and the cost of the pending lawsuit, left the Board with no other choice than to sell Barrington. Businessman Roger Hailstone bought the hall for 2.25 million dollars but failed to rent enough rooms to cover his costs and soon went bankrupt.9.81 The bank foreclosed on the property and the U.S.C.A. was again in possession of Barrington. This time they leased the building to Arthur Hoff for 30 years with the option to end the lease after 10 and after 20 years.9.82

What is Barrington’s Legacy?

Despite the strong sense of community among Barringtonians and their ability to thrive on the alternative lifestyle they had over several years created, the Barringtonians could not exist in their cultural bubble for long. The house was located in a densely populated area where people must actively cooperate to live together peacefully. Their house was located in a residential neighborhood where people desired a quiet place to live which could not be found next door to Barrington. The house was a part of an organization whose viability depended on maintaining a good reputation in the community and among members. As much as the Barringtonians thought of themselves as antithetical to it, they were intimately connected with the mainstream culture that surrounded them.

Most Barringtonians did desire to cooperate to keep their community alive; after all, they made actual changes in their behavior. Perhaps, given enough time, these changes would have helped the house adapt to survive. But working against them was their unwillingness to give up the part of their lifestyle that they perceived as their legacy and essential to their identity. They refused to give up their claim to an alternative lifestyle, which included the uninhibited use of drugs. This part of their identity was what those who fought against Barrington objected to. Perhaps the Barringtonian argument of “there are more of us than you, so we can do what we want” caught up with them. Only this time the neighbors, the City of Berkeley, the University, the media, other community members, and other U.S.C.A. members joined to create a majority that was greater than Barrington.

Barrington was able to hide behind the veil of the slow paced, often lenient U.S.C.A. system for several years. In the process, the house tarnished the reputation of the organization and mocked many of its principles. How to deal with the house split U.S.C.A. members. But Barrington also forced the U.S.C.A. to look at itself and reshape its views. The organization took steps to prevent future major infractions. After Barrington, regulations restricting parties and alcoholic beverages were instituted. New safety codes were passed. When the U.S.C.A. later experienced similar but less extreme problems with its other two large houses, Cloyne Court and Casa Zimbabwe, the organization dealt with the situations in a more direct, timely fashion.

Despite all of the problems it caused, with the loss of Barrington, the U.S.C.A. and Berkeley have been deprived a valuable asset. As a judge in the Orfali-Potter lawsuit described, Barrington was “the last rampart” of sixties counterculture in Berkeley, California. This place to partake in an alternative experience was rejected in favor of conformity. Fortunately, Barrington continues to live as a legend. Many U.S.C.A. members today look at Barrington as mythical and are inspired to see a small hart of Barrington in their own houses. Shut down but not forgotten, Barrington lives in the hearts of many.

Pictures

All of the following photos are by Mahlen Morris

Footnotes

- ... housing.7.1

- Guy Lillian, A Cheap Place to Live, University Students’ Cooperative Association Library, Berkeley, CA.

- ... complexes.7.2

- Ibid.

- ... students.7.3

- Interview by author of George Proper, on March 26, 2002 (notes in author’s possession).

- ... Hall.7.4

- “History of the U.S.C.A.,” Toad Lane Review, April 8, 1983, U.S.C.A. Library, Berkeley, CA.

- ... housings.7.5

- ‘Mission of the USCA,” USCA Owner’s Manual: 1983, U.S.C.A. Library, Berkeley, CA.

- ... movement.7.6

- David Thompson, Weavers of Dreams, Davis, CA: Center for Cooperatives, University of California, 1994.

- ... organizations.7.7

- “Rochdale Principles,” U.S.C.A. Owner’s Manual, 1983, U.S.C.A. Library, Berkeley, CA.

- ... Manual.7.8

- “Co-op Members and University Defunct,” Toad Lane Review, April 8, 1983.

- ... principles.7.9

- Barrington Hall Constitution and By-laws, Barrington Hall miscellany, 308W.U592.bar, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

- ... vote.7.10

- “USCA Board,” USCA Owner’s Manual 1983, U.S.C.A. Library, Berkeley, CA.

- ... made.7.11

- Barrington Constitution.

- ... house.7.12

- Ibid.

- ... members.8.1

- Ibid.

- ... U.S.C.A.8.2

- Guy Lillian

- ... builders.8.3

- Ibid.

- ... students.8.4

- George Proper

- ... autonomous.8.5

- “Onngh Yanngh on Campus,” Toad Lane Review, February 1980.

- ... in.8.6

- Appeal for the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in the Case Ruth Oscar and Charles Spinosa vUniversity Students Cooperative Association, U.S.C.A. Library, Berkeley, CA.

- ... want.8.7

- George Proper.

- ... culture.8.8

- “Letter about Barrington,” Toad Lane Review, May 10, 1984.

- ... themselves.8.9

- “Opinion of other houses and what people do and do not like about the co-ops,” Toad Lane Review, May 10, 1984.

- ... room.8.10